Meet A Man With

Eight Hundred Banks

DORIS ANN KRUPINSKI, HOBBIES, March 1955

Imagine

owning nearly a thousand banks yet not being a

millionaire. That's the case with a

Milwaukee man,

but he's had a million dollars worth of fun

from his toy bank collection.

JOHN JOHANNSEN of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has money in nearly 800 banks. In fact, he has

several thousand dollars in his banks. And yet, if he withdrew the money from every one of

them, it would only amount to a small pile of pennies.

It is the banks themselves that are worth several thousand dollars, for Johannsen is a toy

bank collector. He recommends the hobby as a source of fun and profit to everyone,

regardless of age, as long as they are "young at heart."

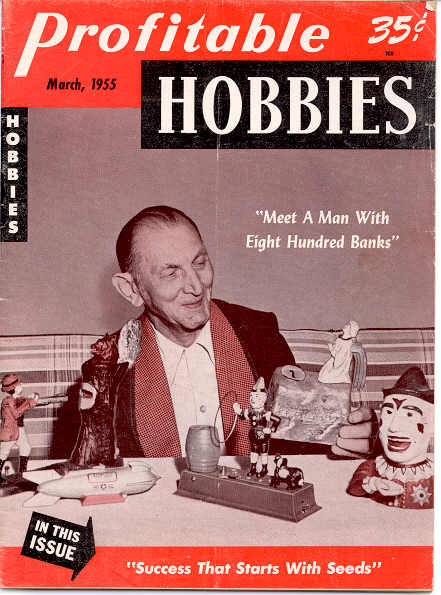

JOHN JOHANNSEN with a part of his bank

collection, which fills the upper floor of his home.

The banks are placed on the shelves according to type. Johannsen keeps a record

of each bank

that tells how much it cost, where it was purchased, the dates on which it was

last cleaned,

and other pertinent facts.

Many of the banks in Johannsen's collection are the old mechanical banks which provided

such a pleasant way of saving money a couple of generations back. A penny inserted in the

slot of any one of these banks produces amusing and sometimes noisy results.

The William Tell bank, for instance, uses a real cap, which explodes noisily when William

Tell fires a penny at an apple on his son's head. If the penny hits the apple, a window in

the iron tower at the rear opens, and the penny is deposited through it. If it misses, as

it sometimes does, you have the fun of shooting again.

In a variation of this, called Teddy and the Bear, Teddy Roosevelt fires a penny into a

slot in a tree stump, causing a brown bear to pop out of the stump.

THIS IS THE POPULAR JONAH and the Whale bank.

Jonah, safe

in a little boat, feeds the coin, instead of himself, to the whale.

WHILE THESE old mechanical banks were supposedly to encourage children to save money, many

of them have themes which only adults can appreciate. The "Tammany" bank is a

portly politician with outstretched hand, who takes a coin in his palm, flips it into his

pocket, nods his head in thanks, and extends the hand again.

The Reclining Chinese holds a hand of cards against his breast. As he takes a coin with

one hand, he shows the royal flush which he holds in the other.

More truly for the amusement of children is the Eagle and Eaglets bank. This one contains

a bellows in the base which causes the two baby birds to chirp when their mother feeds

them a coin.

In addition to the mechanical banks, Johannsen's collection contains many which are termed

"semi-mechanical." This category includes such banks as miniature automobiles

and railroad cars, whose moving parts have nothing to do with the insertion of the coin.

Many register banks are also classed as semi-mechanical.

By far the greatest percentage of the collection consists of still banks, ranging in size

from the Sunday School bank, which is about as big as a candy mint, to a "combination

safe" which is a cubic foot in size. These still banks come in a variety of shapes:

figures, houses, mail boxes, animals, famous buildings, and many others. Figures are about

the hardest to come by.

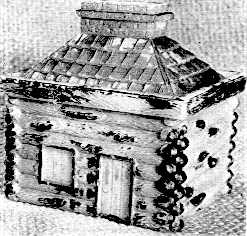

THIS PORCELAIN LOG CABIN BANK, dating back to

about 1793, once held tea,

which had to be shaken out of the coin slot in the chimney before the container

could be used as a bank.

TO BE a successful bank collector, says Johannsen, it is necessary to be a specialist. If

you try to make banks just one of the many collections, you will not become familiar

enough with them to know what fair prices are - and you'll find yourself paying too much

for each item.

If you make banks your main hobby, you will concentrate your energies on becoming expert

on the subject - and this expertness soon has an effect on the amount of profit you make.

Johannsen gives this advice out of his own experience. For many years before he became a

bank collector, he scattered his shots in the field of collecting.

"From the time I was a boy in Germany," he says, "I collected anything I

could get my hands on. Much of it would be thrown away by my parents; I'd retrieve it, and

they would throw it away again.

"When I got older, I used to haunt antique shops, buying anything that took my fancy

- and just about everything did. My wife used to call a lot of it 'Junk.' She didn't much

trust my judgement."

White-haired, twinkle-eyed Mrs. Johannsen adds with a good-natured sigh, "He just

couldn't leave antique shops alone!"

THE WILLIAM TELL BANK uses a real cap, which

goes off noisily when the coin is

shot into the window just behind Tell's son's head. Don't ask why Mr. Tell is

using a

gun instead of a bow and arrow.

As a result of all this, the Johannsen home itself eventually came to look like an antique

shop. Glassware, china, coins, stamps, dolls, playing cards, steins, were all stirred into

an indiscriminate collection that had no form or direction.

There was a handful of banks among the other things, but until a warm August afternoon in

1937, the banks held no more and no less interest for Johannsen than the other items he

had collected.

Then, on Sunday, August 4, 1937, Johannsen went to look at some items another antique

collector had for sale, and was fascinated by five mechanical banks the man was offering.

Undaunted by the fact that the collector would only sell them as a group, along with

fifty-two still banks, he bought the whole lot - and had the beginning of his present

collection.

THIS IS JOHNANNSEN'S "BIG FLOP" — a

toy which he purchased believing it to be

a bank. When he discovered it was merely a mechanical toy, he removed the

operating lever and altered it so that it required insertion of a coin to work.

(Slot

which once held the lever can be seen at the rear of the base.) While it is not

really a bank, Johannsen likes to have it around as a constant reminder to

investigate what he is getting before he pays for it.

ONCE JOHANNSEN decided to specialize in toy banks, he disposed of most of the other things

he had collected and set about becoming an expert.

He dismantled the mechanical banks, piece by piece, cleaned, adjusted, and oiled them, and

thus became familiar with the working mechanics of each. He still does this whenever he

acquires a new bank, and twice a year thereafter. As a result, every item in his

collection is in top condition, a prime factor when reckoning value.

Some banks must be adjusted very precisely, or they will be damaged when used. The 'Spise

A Mule bank, for example, is often found in broken condition because of the low adjustment

tolerance.

"A bank which has been repaired or repainted, or is not in the original mechanical

condition , loses value," says Johannsen. "Sometimes you meet a collector who

has decided that the dull iron and chipped paint of his banks need brightening - and he

has painstakingly repainted them in the modern enamels. By doing so, he has reduced the

value of his collection by a third or more."

It is not always great age which determines the value of a bank, but rather the rarity.

Many of the older mechanical banks, dating back to 1870 or so, were made of such sturdy

cast iron, and sold in such great quantities, that large numbers of them still survive.

Among these are the Tammany, Cabin, and Eagle banks.

In contrast, banks of the 1880-1890 period, being often of more fragile materials, are

hard to find, and bring correspondingly higher prices.

Rarest of all are the single specimen banks, which are samples of designs that never

reached the production stage. A bronze model of a bank patented but never manufactured was

sold to a Milwaukee dealer for $600 recently. He in turn asked $750 for it!

THE LIGHT OF ASIA BANK, valued at $150, nods

its head in thanks when a

coin is inserted in the slot on its back. This is an example of a bank now worth

much more than Johannsen paid for it.

JOHANNSEN, WHO collects toy bank patent papers as well as the banks themselves, finds that

a great many banks were designed and patented, but never made. Since the toy banks had to

please the parents who bought them even more than the children, a design that seemed

destined for sure fire popularity sometimes fell flat on its face.

Bank manufacturers, then, were understandably cautious about the banks they produced.

Making the original sample bank from the patent papers was a costly process, and it would

take a great many twenty-five-cent to one-dollar bank sales to retrieve the investment.

Making a simple bank was done by first making a solid wax model of the bank, from which a

plaster of Paris mold was taken in two parts. From these molds, two hollow wax molds were

made.

HERE ARE THE LARGEST AND SMALLEST banks in

Johannsen's collection.

At the left is the tiny Sunday school bank, which holds ten dimes. The Safe

bank, a cubic foot in size, opens with a combination lock.

The next step was to remove from the wax model all the parts which were intended to be

movable - the arms of the politician, the leg of the kicking mule, the jaw of a man, and

often the eyes of the figure. A new model of each of these parts then had to be made with

an end or joint attached to it. All the separate pieces were then sent to a foundry to be

cast in bronze.

When the bronze pieces came back, some of them were very rough and had to be filed and

chased to make them fit into each other. The pieces of the assembled bronze model had to

fit together perfectly and move easily, or the cast iron banks then made from the model

would not work properly.

It is easy to see why a manufacturer might hesitate to go through this lengthy and

expensive process if he had any doubt as to the salability of the bank.

One of the banks in Johannsen's collection was made for him from the original patent

papers. It is a miniature wooden bureau, the top drawer of which accepts the coins. The

drawer is pushed in, and when it is withdrawn again, the coin has disappeared into the

bank's secret compartment.

ALTHOUGH JOHANNSEN considers the mechanical banks the stars of his collection, there is an

even brighter star - his favorite bank. It is a German "Mission Bank," with

kneeling angel who nods her head in thanks when a coin is dropped into the slot of a

golden plate on the grassy hill on which she kneels.

"I believe I am the only collector in the country who owns such a bank," he

says. "I wouldn't put a price on it. It is priceless."

The rarity of the bank is not the factor that endears it to Johannsen. Actually, it

personifies childhood memories of his native Germany. The little Lutheran church to which

he belonged had a similar bank - with a little Negro boy instead of an angel - to

encourage children to give money for foreign mission work.

When he began to collect banks, he searched for the bank of his childhood, but in vain. He

did find the angel mission bank in an antique shop, and the dealer presented it to him as

a gift.

"But I still wanted the Negro foreign-mission bank," he says, "and when we

were in Germany in 1952, my wife and I went to the little church to see if it was still

there."

"It was there, all right," puts in Mrs. Johannsen, "but they wouldn't sell

it. The children were still faithfully putting their pennies into it every week, and the

pastor said the church just couldn't afford to part with it."

Johannsen still hasn't given up hope of someday obtaining such a bank, however. It is one

of the fascinating peculiarities of collecting that you never know when an exciting find

is just around the next corner. It gives the collextor something to look eagerly forward

to each day. It keeps the spring in a man's step and youth in his eyes.

THERE ARE a number of sources of banks which Johannsen checks regularly in order to add to

his collection. First, of course, he visits antique shops wherever he goes. Whether or not

a shop has any banks for sale at the time of his visit, he leaves his name, address, and

telephone number, with the request that he be notified when banks - mechanical or still -

come into the shop.

Another source of banks are auctions, which often produce an item considered of little

value by the owner or auctioneer, and which can be purchased at a low price.

A word here about the term "value." The value of a bank, like most collector's

items, is generally only what another collector is willing to pay for it. That is why

Johannsen advises specializing in banks alone, in order to familiarize yourself with the

amount a bank is worth to a collector.

Value depends on a bank's condition, scarcity, and mechanical action. There are also small

differences between apparently similar banks which can mean large differences in the

bank's worth. Different types of coin traps, different wording on the banks, different

manufacturers - all are variations which a collector should understand in order to

estimate accurately the value of his banks.

"Although I've made profitable purchases of most of my banks," says Johannsen,

"I was stung a few times at first, because I did not know the value of a bank, or

because I had set my mind on having it, and overpaid.

"But I have also, I regret to say, passed up opportunities to buy because I had my

mind set on a price not to be exceeded. If I had at that time been more familiar with

prices, I would have known that even some seemingly high prices were actually less than

the value of the bank."

Johannsen relates a classic example of a collector obtaining a number of banks at less

than their value. "My collector friend, who lives in Indiana, started collecting in

1937, as I did," says Johannsen, "and had a real stroke of luck in 1941 that put

him on the map in a hurry. Driving through the eastern states, he stumbled on to an old

man who sold him 175 different mechanical banks in perfect condition for $1,245, an

average of $7.11 per bank. His ultimate profit on the transaction was at least

tenfold!"

FORTUNATELY, THE person who wishes to begin collecting banks can now refer to two

excellent books, available in many large city libraries, which give him information it

took Johannsen years to acquire. The first is "Old Mechanical Banks," by Ina

Hayward Bellows, published by the Lightner Publishing Company of Chicago in 1940. This

book lists and describes a great many banks, and gives their valuation as it was in 1940.

Most of the banks have risen in value since that time, however.

The second reference book is "A Handbook of Old Mechanical Penny Banks," by John

D. Meyer of Tyrone, Pennsylvania, published in 1947. This book has photographs and

descriptions of all known mechanical banks, plus some indication of their worth, such as

"Very Rare" or "Common." Because of the rising value of the banks,

Meyer does not attempt to put a precise valuation on each.

A small booklet which was recently published is probably the most helpful of all, because

it gives the value of each bank as judged by each of the several experts in the field, and

lets the bank collector judge for himself. It is entitled "Old Penny Mechanical Banks

Price List, Including Gradations of Prominent Authors." This booklet, which is

available at $1 from Henry W. Miller, 29 Lincrest Street, Hicksville, Long Island, New

York, does not contain pictures or descriptions of the banks, but only the names.

EVEN BECOMING an expert is not always a safeguard for the too-avid collector. Johannsen

has a "football bank," which he keeps around to remind him of what can happen

when he tries too hard to get a bargain.

One day, a couple of years ago, one of his daughters went to a rummage sale - another

prolific source of banks - to see if there were any items of interest. She came back to

say that there were two banks - one of them a football player.

"I had wanted a football player for a long time," recalls Johannsen, "so I

rushed right over to the church and bought both banks. I paid quite a bit for the football

player, but nowhere near the actual sale value of such a bank. I came home elated with my

bargain.

"I showed the bank to my wife -" he paused to take the bank off a shelf, "-

it's this little football player who kicks a tiny ball attached to a string when a lever

is pushed. My wife looked at is a minute, and then asked, 'But where do you put the

penny?'

"And do you know," he chuckled ruefully, "there was no slot for a penny! It

wasn't a bank after all - just a mechanical toy!"

Johannsen subsequently altered the football player so that it became a bank. He does not

consider it a part of his authentic collection and it could never be sold as a bank - but

he feels that having it around keeps him humble.

THE SALVATION ARMY and Goodwill stores found in most large cities are also good sources of

banks. These organizations are constantly receiving years' accumulation of junk from

people's attics - and all kinds of old banks turn up frequently. If it isn't convenient

for the collector to visit the stores frequently, he might ask one of the salespeople to

notify him when a bank comes in.

"This is such a good way of finding the really rare banks," says Johannsen,

"that a doctor friend of mine, who is now dead, used to go to the Milwaukee Goodwill

store near his office three times every day. He found some very good banks that way."

For Johannsen, who is not given to superlatives, "very good" is the top

classification in his collection.

Buying banks at prices lower than their value makes a collection potentially profitable,

if a collector should ever decide to sell. It just happens that Johannsen does not intend

to sell any of his collection of 786 all different banks at any price, but he does have

many duplicates, which he sells to other collectors.

"I buy almost any bank I come across," he says, "because I know all the

collectors in Milwaukee, and can usually sell the duplicates."

Since Johannsen is not out for a profit, he sells the banks to collectors at the price he

paid for them - sharing with these collectors the opportunity to add to their collections

at reasonable prices. There are many bank collectors, however, who do conduct such re-sale

of banks at a high profit.

Selling at a profit is not the only way to earn dividends on an investment, however.

Merely holding the banks for a few years increases their value. One bank which sold for

$1.50 several years ago when it was new is now worth $16.00. Even the very modern banks -

such as the "Bomb Hitler" and "Lick the Axis" banks of World War II -

are fast becoming collector's items, and will some day be worth many times their original

cost. It is the same with the toy banks given out by large banks and building-and-loan

companies to their customers.

ONE SECTION of Johannsen's bank-filled upstairs room is devoted to the tin, plastic, and

glass banks his grandchildren give him on birthdays and at Christmas, These have only

sentimental value at present, but they may some day be worth a great deal.

Among the many unusual banks on Johannsen's shelves are two coconut banks, intricately

carved and polished - one worth $50, the other worth about $40. The difference lies in the

fact that the coin trap of one of the banks was missing when he found it in a Chicago

antique shop. You wouldn't know which one, however, if Johannsen didn't tell you. In order

to complete the bank with the missing part, Johannsen bought a coconut and painstakingly

carved and polished a coin trap to match the rest of the bank.

"It took me many long hours to complete that little coin trap," he says,

"so you can imagine how long it must have taken to carve the whole coconut."

One of the most valuable banks in his collection is the Light of Asia, a cast iron

elephant who nods his trunk when a coin is inserted in his back. This is worth $150 - much

more than Johannsen paid for it.

A bank of which Mr. J. is particularly proud is the Southern Comfort bank, put out by a

whisky manufacturer, The president of the company, who happened to be a toy bank collector

himself, issued just 1,000 of these silver-plated banks, individually numbered, and

offered them privately at a nominal fee to known collectors. Johannsen has a notarized

affidavit showing that he was issued bank number thirty-one.

An enameled version of the Southern Comfort bank was later offered to the general public

through advertisements in hobby magazines, but these are worth only a fraction as much as

the silver-plated originals.

MR. JOHANNSEN regards advertisements in hobby and antique magazines as prime sources of

items for a bank collection. The collector can run his own advertisements in the

"Wanted" columns of the magazines - or he can check the "For Sale"

advertisements of the dealers.

By watching the advertisements he gets to know the names of other collectors throughout

the country, and mutually profitable trades can often be worked out.

Johannsen once traded thirty-two surplus mechanical banks for just three from another

collector - and felt that it was a fair bargain because of the quality of the three banks.

Even the least valuable of the three, a Pelican bank, is worth $95, and the others worth

more.

Johannsen keeps an account book in which he records the price and the source of each new

bank he gets for his collection, together with manufacturing and patent data.

After a collector has accumulated a few items, he will often want to display them at

school or club hobby shows. This, according to Johannsen, is another way of building up a

collection. No matter how small the hobby show, someone invariably tells him, "Why,

I've got an old bank somewhere around the house. I'll sell (or, in rare cases, 'give') it

to you."

Since hobby shows are often reported in local newspapers, there is a good chance that

individual exhibitors will receive special attention in feature articles. Johannsen has

been written up several times in both Milwaukee papers, and each article was picked up by

the press services and reprinted in newspapers in other large cities.

Each newspaper article brings him information about other banks which are being offered

for sale.

Johannsen's appearances at hobby shows have also led to publicity on television shows. The

antics of a few mechanical banks would provide enough action to keep a TV show lively,

even if Johannsen weren't the enthusiastic speaker he is. Each such appearance brings

Johannsen's name before the public so that people automatically think of him when they run

across a bank.

"These are the contacts which make it possible for a collector to get at the banks

stored away in people's attics," says Johannsen. "The hardest thing for a

collector is to gain admittance to private homes. You can't just go around ringing the

doorbells of old homes asking if people have any banks in the attic. They'd think you were

crazy! But if you become well known in your community through publicity, people will come

to you instead."

A BANK collection need not be confined to the banks of the last century, which was the

heyday of the mechanical variety. The really avid collector can go much farther back than

that and build up an extremely valuable collection.

Saving money dates back to ancient Greece, where pottery urns were used. Pottery and

porcelain still banks were also known in Europe at a very early date. The first known

mechanical bank is an alms box of China's Han dynasty, which was just before the Christian

era. This bank is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Imagine how exciting it would be to obtain one of these museum pieces for one's

collection!

Penny banks first appeared in America in 1793, along with the first big copper pennies.

These banks were usually of pottery, glass, or tin, and often held tea or honey before

they were emptied to be used as banks.

Johannsen has a porcelain reproduction of a log cabin, with an opening in the chimney

barely large enough for the insertion of a coin. This originally was a tea container, and

the housewife who wanted to use the tea had to shake it out, a little at a time, through

the chimney!

When this type of bank was filled with coins, the only way to remove them was also through

the chimney, one by one - unless the owner was in a hurry, in which case he could simply

take a hammer to it.

Some of the glass banks of this period are collector's items in another field - that of

glassware. Johannsen has, among others, a glass reproduction of Independence Hall in

Philadelphia, made in 1875, and molded in three parts, instead of the more common two

parts. For this reason, the bank is doubly valuable.

BEN FRANKLIN, with his "Poor Richard's Almanac," greatly influenced the American

people so that saving became a national habit. Nowhere else in the world was the toy bank

as popular as it was in America.

Americans had a reputation abroad for "squeezing the eagle until it screamed."

It might be noted, however, that European manufacturers tried their best to profit from

America's thrift by exporting a great many tin banks for sale on the American market.

After the Civil War, however, when foundries stopped making war material and looked for

new fields, the more fragile tin banks were swept off the market by the appearance of the

sturdier cast-iron banks, which could be made in such varied shapes.

Somewhere around the turn of the century, it became common for bankers - real bankers,

that is - to collect toy banks. Some of the most fabulous collections in the world were

amassed by these men. To this day, the best collections are owned by bankers, such as

Andrew Emerine, president of the First National Bank of Fostoria, Ohio.

Industrialists too, such as Ford and Chrysler, were given to the collection of banks.

"Those men could have all the best banks if they wanted them," Johannsen says a

bit wistfully, "because they didn't have to consider price."

There are banks still in existence today, perhaps in somebody's attic, which are valued at

$1,000 or more. The dream of every bank collector who is not a millionaire is to find one

of these banks for sale at a reasonable price.

In the meantime most of them, like Johannses, are content to collect the exciting

mechanical and still banks that tell the history of our nation. The story of banks is the

story of free enterprise, the rags to riches, of Horatio Alger - of the freedom to improve

one's status that is characteristic of America.

EMERINE COLLECTION

ON EXHIBIT

The First National Bank of Fostoria, Ohio, recently placed on

exhibition an outstanding Coin Bank Collection representing the kind of banks

youngsters treasured eighty years ago.

Most of the banks are made of cast iron, and date from 1870 to 1900. They were

the principal produce of several eastern foundries, Stevens Foundry at Cromwell,

Conn., being the largest producer, according to a bulletin on the Collection

published by The First National Bank, and sent out by Mr. and Mrs. Andrew

Emerine of Fostoria.

Many characters and subjects were represented in these banks, including

biblical, historical, comical, sports, also Chinamen, Indians, Irishmen, Red

Riding Hood, William Tell, Christopher Columbus, Uncle Sam, Teddy Roosevelt,

John Bull, Jonah and the Whale, and, among the animals, elephants, frogs, and

pelicans.

Emerine especially prizes the Freedman Bank made at Bridgeport, Conn. Other

interesting ones include The Bread Winner Bank, the Merry-Go-Round, the Carnival

Bank, The Harlequin Bank, and Shoot the Chute with Buster Brown and Tigue.

English Banks include John Bull Money Box and Wimbledon obtained at Norwich,

England.

Besides banks, the Museum has a display of Automatona, including musical dolls,

acrobats, and walking figures. A boy with a pewter dish containing soap suds

dips his pipe, puts it to his lips, and blows bubbles. U. S. Grant seated in a

chair smokes & turns his head and puffs out smoke. A woman is busy churning.

A lady works at a wash-tub over a washboard . A bird sings in a gilded cage.

Rare sand toys also are shown. A toy turning upside down trickles sand down on a

cardboard wheel, action is transmitted to figures, and banjo and violin players

go into action, so do the dancer and dog.

Thirty years ago many of these items were rather readily available to

collectors, but now they have become very rare and the price has correspondingly

raised, as is typical of many a Collector's item.

MCCALLS - May 1953

COLLECT SMALL ANTIQUES

Mechanical banks

by Katharine M. McClinton

Author of Antique Collecting for Everyone

TIN and cast-iron children's coin banks were

popular from about 1860 to 1910. They are still made.

Mechanical banks work when a coin is inserted in a slot. The most popular ones

are animals including dogs, cats, elephants, frogs, owls, turtles, lions and

alligators. Some are replicas of historical objects. Others are miniatures of

Punch and Judy, Little Red Riding Hood, Santa Claus, Jonah and the Whale and the

Old Woman in the Shoe.

The most commonly seen today are the Harlequin and Columbine, Speaking Dog,

Kicking Mule, William Tell and Humpty Dumpty. The rarest include the British

Lion, Girl in Victorian Chair, Battleship Masachussetts, Ferris Wheel, Bowling

Alley and Fortune Teller. Most are painted or enameled.