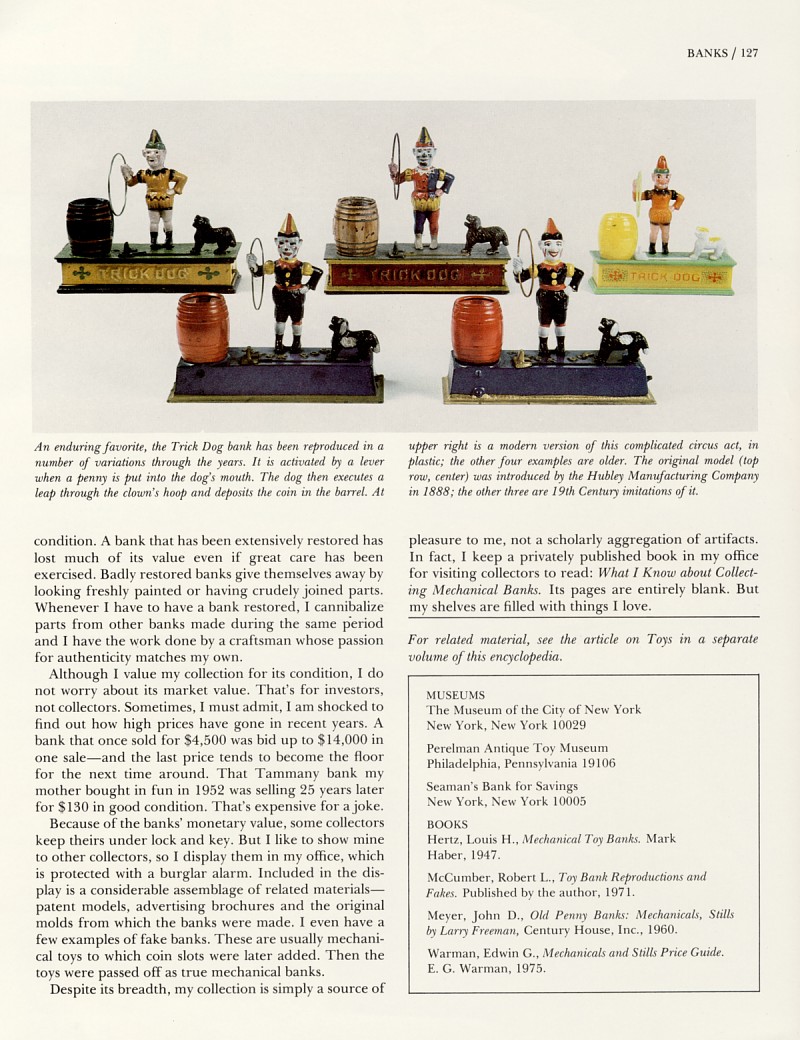

|

Banks

Making a Game of Moneysaving

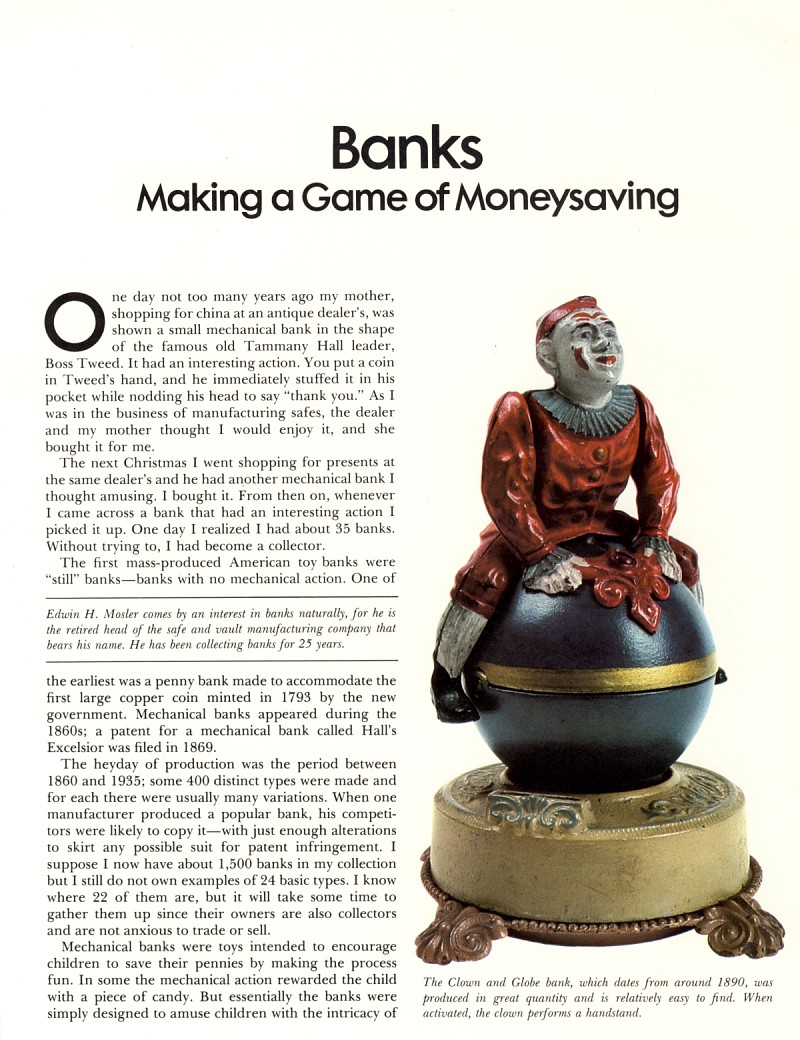

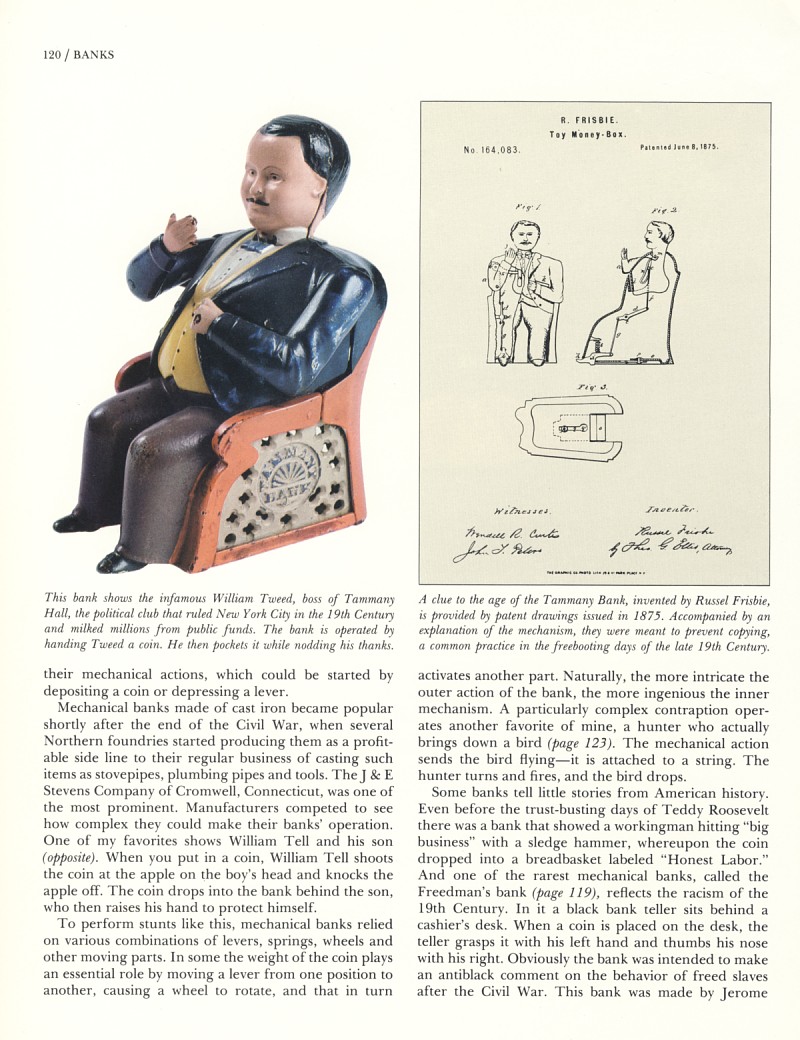

One day not too many years ago my mother, shopping for china at an

antique dealer's, was shown a small mechanical bank in the shape of the

famous old Tammany Hall leader, Boss Tweed. It had an interesting

action. You put a coin in Tweed's hand, and he immediately stuffed it in

his pocket while nodding his head to say "thank you." As I was in the

business of manufacturing safes, the dealer and my mother thought I

would enjoy it, and she bought it for me.

The next Christmas I went shopping for presents at the same

dealer's and he had another mechanical bank I thought amusing. I bought

it. From then on, whenever I came across a bank that had an interesting

action I picked it up. One clay I realized I had about 35 banks. Without

trying to, I had become a collector.

The first mass-produced American toy banks were "still" banks—banks

with no mechanical action. One of the earliest was a penny bank made to

accommodate the first large copper coin minted in 1793 by the new

government. Mechanical banks appeared during the 1860s; a patent for a

mechanical bank called Hall's Excelsior was filed in 1869.

|

Edwin H. Mosler comes by an interest in banks naturally, for

he is the retired head of the safe and vault manufacturing

company that bears his name. He has been collecting banks

for 25 years. |

The heyday of production was the period between 1860 and 1935; some 400

distinct types were made and for each there were usually many

variations. When one manufacturer produced a popular bank, his

competitors were likely to copy it—with just enough alterations to skirt

any possible suit for patent infringement. I suppose I now have about

1,500 banks in my collection but I still do not own examples of 24 basic

types. I know where 22 of them are, but it will take some time to gather

them up since their owners are also collectors and are not anxious to

trade or sell.

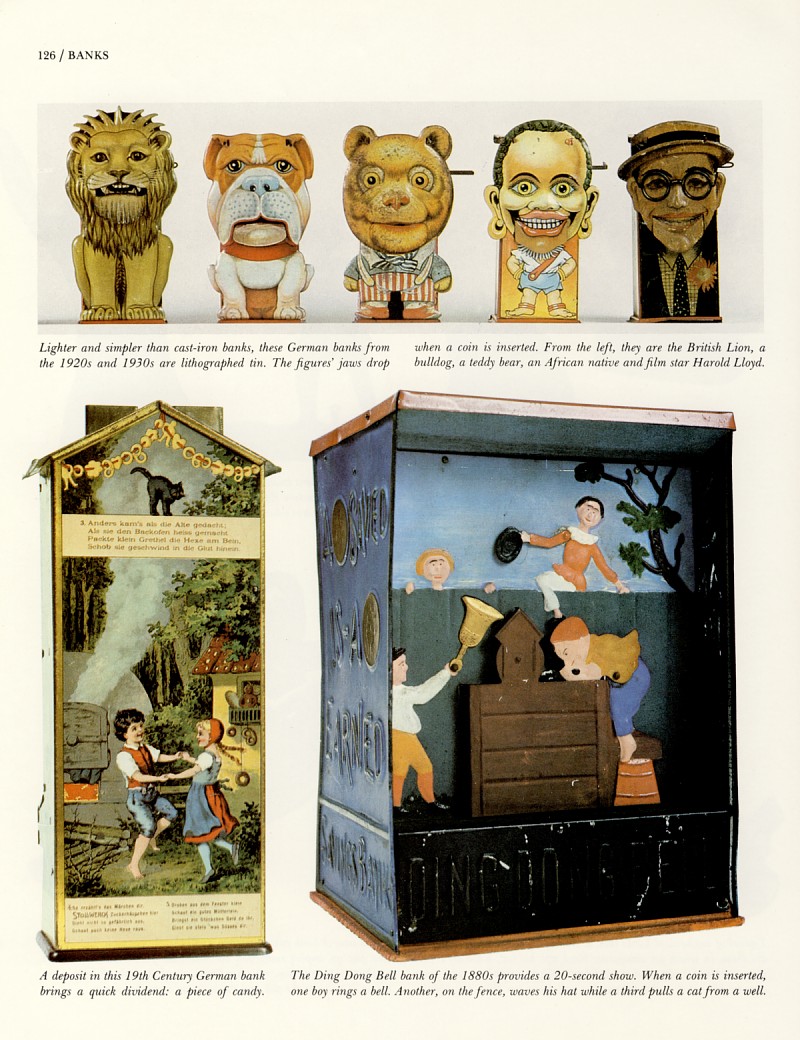

Mechanical banks were toys intended to encourage children to save

their pennies by making the process fun. In some the mechanical action

rewarded the child with a piece of candy. But essentially the banks were

simply designed to amuse children with the intricacy of their

mechanical actions, which could be started by depositing a coin or

depressing a lever.

Mechanical banks made of cast iron became popular shortly after the

end of the Civil War, when several Northern foundries started producing

them as a profitable side line to their regular business of casting such

items as stovepipes, plumbing pipes and tools. The J & E Stevens Company

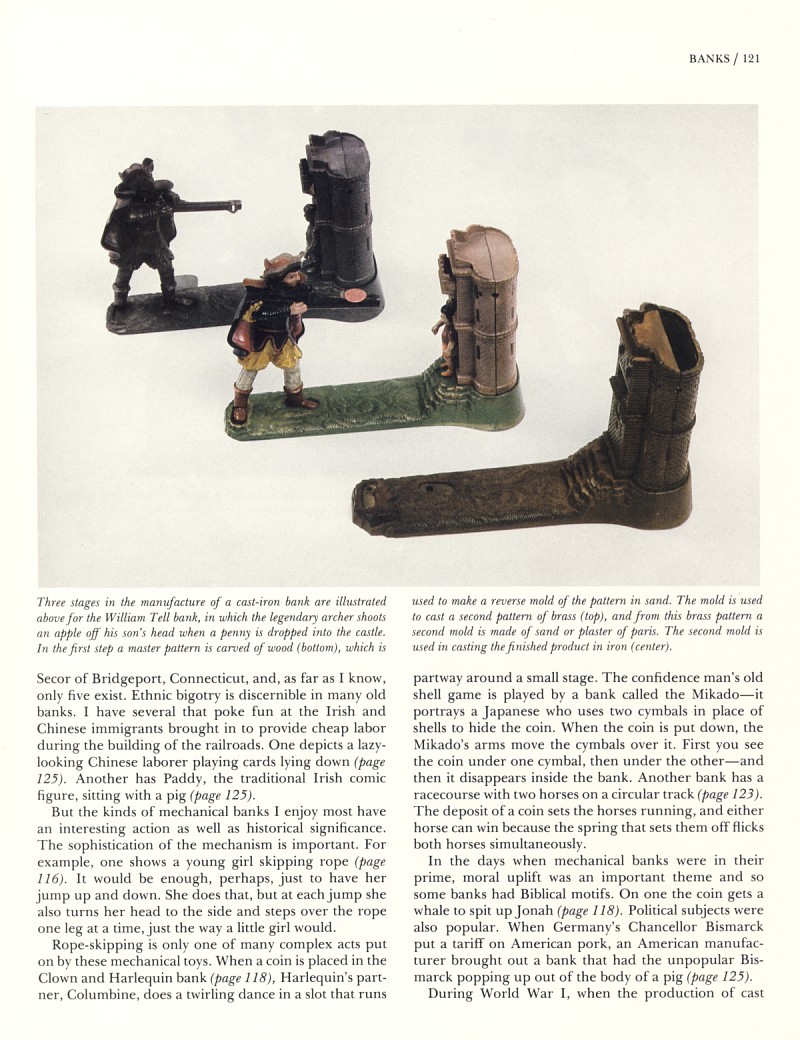

of Cromwell, Connecticut, was one of the most prominent. Manufacturers

competed to see how complex they could make their banks' operation. One

of my favorites shows William Tell and his son (opposite). When you put

in a coin, William Tell shoots the coin at the apple on the boy's head

and knocks the apple off. The coin drops into the bank behind the son,

who then raises his hand to protect himself.

To perform stunts like this, mechanical banks relied on various

combinations of levers, springs, wheels and other moving parts. In some

the weight of the coin plays an essential role by moving a lever from

one position to another, causing a wheel to rotate, and that in turn

activates another part. Naturally, the more intricate the outer action

of the bank, the more ingenious the inner mechanism. A particularly

complex contraption operates another favorite of mine, a hunter who

actually brings down a bird. The mechanical action sends the bird

flying—it is attached to a string. The hunter turns and fires, and the

bird drops.

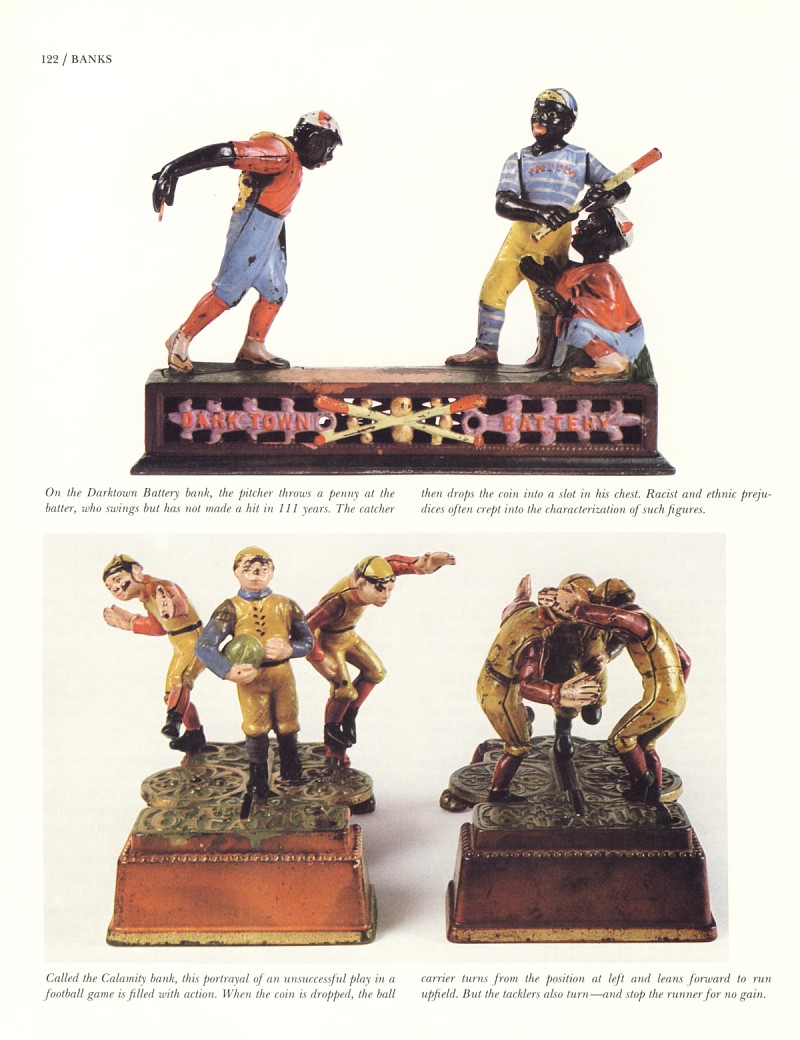

Some banks tell little stories from American history. Even before

the trust-busting clays of Teddy Roosevelt there was a bank that showed

a workingman hitting "big business" with a sledge hammer, whereupon the

coin dropped into a breadbasket labeled "Honest Labor." And one of the

rarest mechanical banks, called the Freedman's bank, reflects the racism

of the 19th Century. In it a black bank teller sits behind a cashier's

desk. When a coin is placed on the desk, the teller grasps it with his

left hand and thumbs his nose with his right. Obviously the bank was

intended to make an antiblack comment on the behavior of freed slaves

after the Civil War. This bank was made by Jerome Secor of Bridgeport,

Connecticut, and, as far as I know, only five exist. Ethnic bigotry is

discernible in many old banks. I have several that poke fun at the Irish

and Chinese immigrants brought in to provide cheap labor during the

building of the railroads. One depicts a lazy- looking Chinese laborer

playing cards lying down. Another has Paddy, the traditional Irish comic

figure. sitting with a pig.

But the kinds of mechanical banks I enjoy most have an interesting

action as well as historical significance. The sophistication of the

mechanism is important. For example, one shows a young girl skipping

rope. It would be enough, perhaps, just to have her jump up and down.

She does that, but at each jump she also turns her head to the side and

steps over the rope one leg at a time, just the way a little girl would.

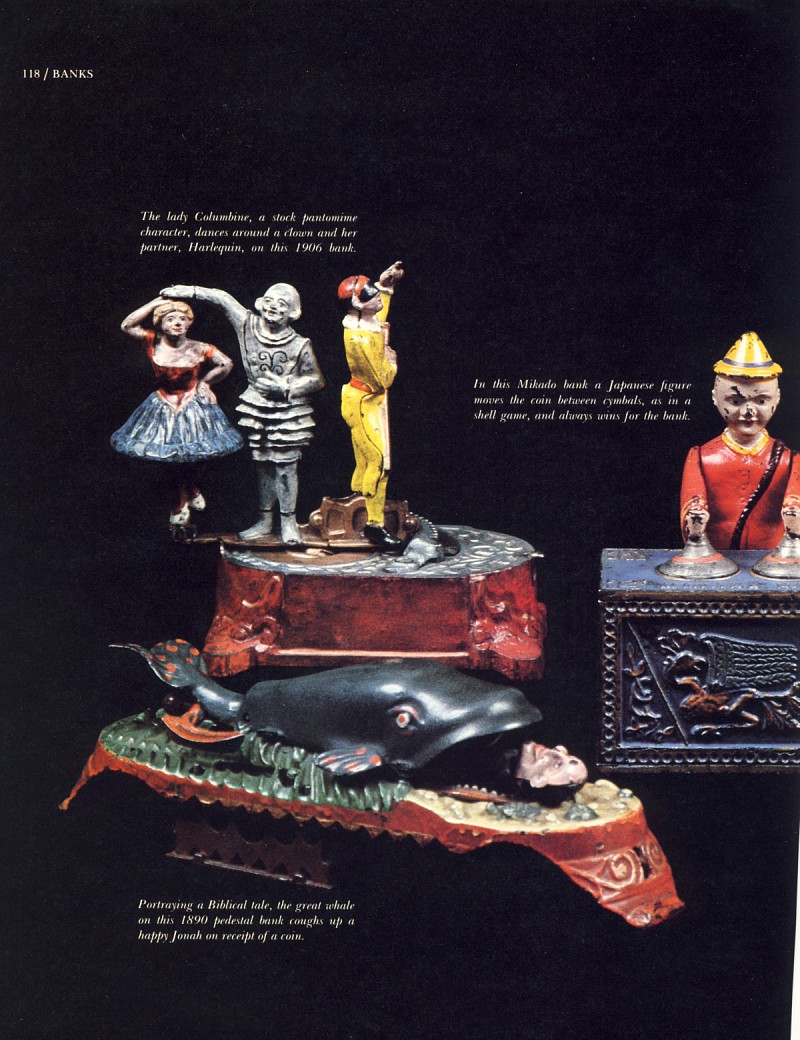

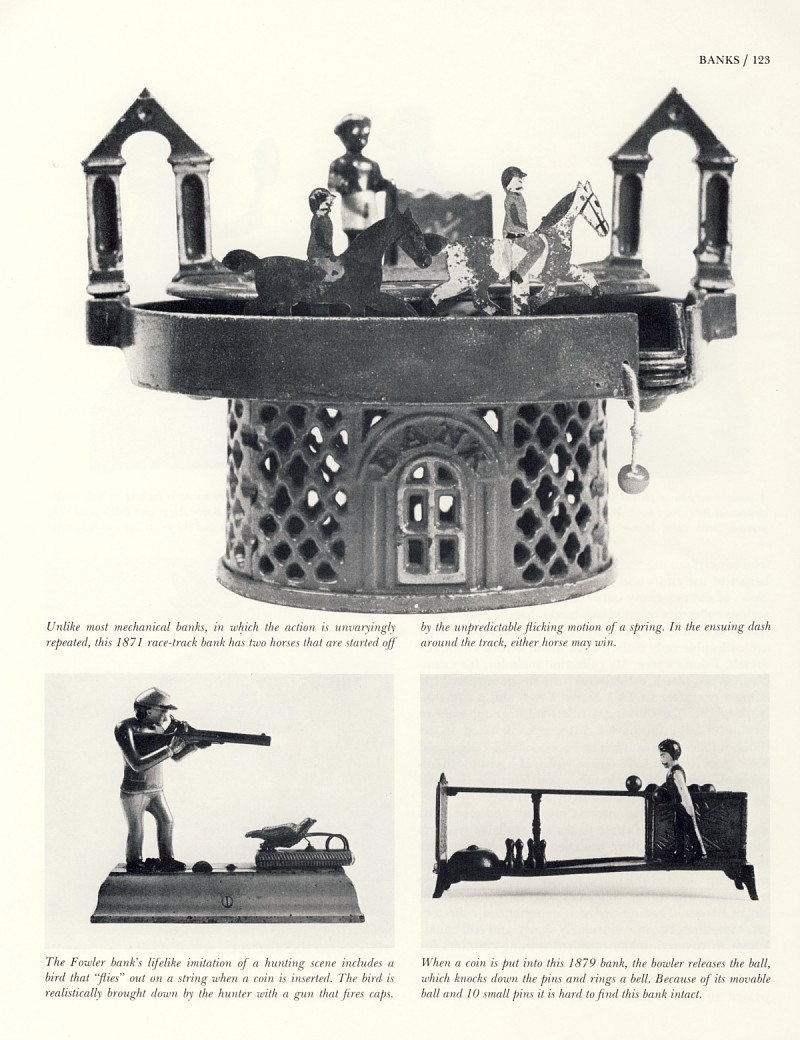

Rope-skipping is only one of many complex acts put on by these

mechanical toys. When a coin is placed in the Clown and Harlequin bank,

Harlequin's partner, Columbine, does a twirling dance in a slot that

runs partway around a small stage. The confidence man's old shell game

is played by a bank called the Mikado—it portrays a Japanese who uses

two cymbals in place of shells to hide the coin. When the coin is put

down, the Mikado's arms move the cymbals over it. First you see the coin

under one cymbal, then under the other—and then it disappears inside the

bank. Another bank has a racecourse with two horses on a circular track.

The deposit of a coin sets the horses running, and either horse can win

because the spring that sets them off flicks both horses simultaneously.

In the days when mechanical banks were in their prime, moral uplift

was an important theme and so some banks had Biblical motifs. On one the

coin gets a whale to spit up Jonah (page 118). Political subjects were

also popular. When Germany's Chancellor Bismarck put a tariff on

American pork, an American manufacturer brought out a bank that had the

unpopular Bismarck popping up out of the body of a pig.

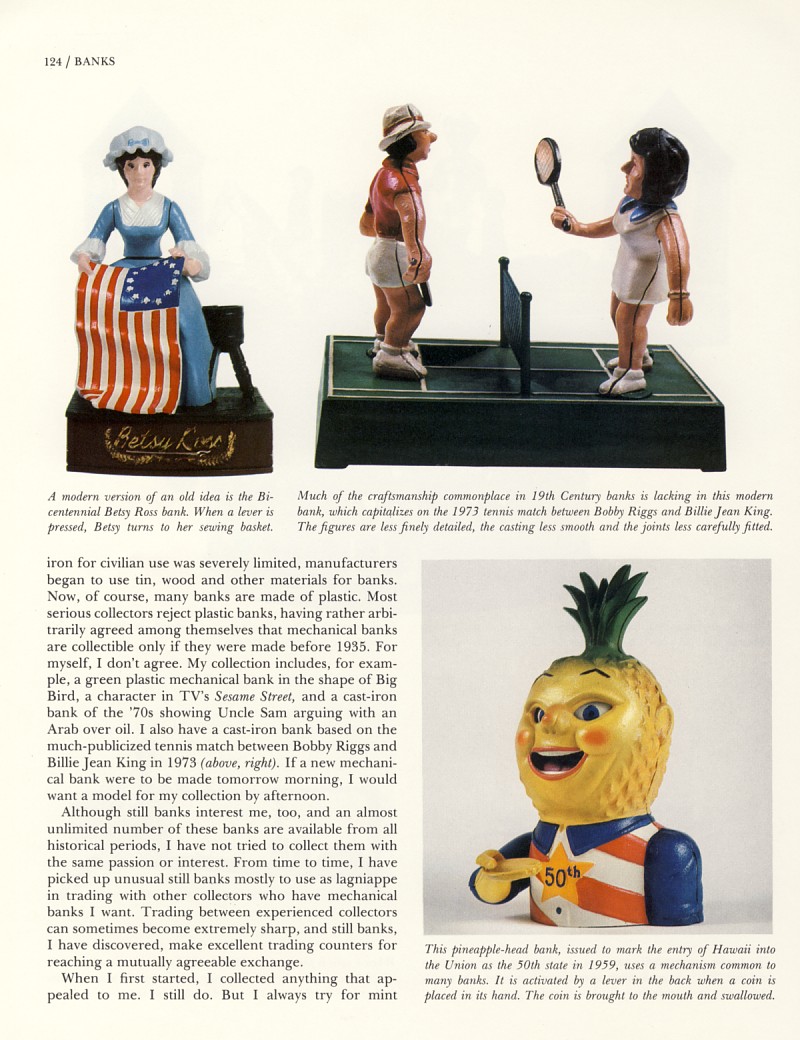

During World War I. when the production of cast iron for civilian use

was severely limited, manufacturers began to use tin, wood and other

materials for banks. Now, of course, many banks are made of plastic.

Most serious collectors reject plastic banks, having rather arbitrarily

agreed among themselves that mechanical banks are collectible only if

they were made before 1935. For myself, I don't agree. My collection

includes, for example, a green plastic mechanical bank in the shape of

Big Bird, a character in TV's Sesame Street, and a cast-iron bank of the

'70s showing Uncle Sam arguing with an Arab over oil. I also have a

cast-iron bank based on the much-publicized tennis match between Bobby

Riggs and Billie Jean King in 1973. If a new mechanical bank were to be

made tomorrow morning, I would want a model for my collection by

afternoon.

Although still banks interest me, too, and an almost unlimited

number of these banks are available from all historical periods, I have

not tried to collect them with the same passion or interest. From time

to time, I have picked up unusual still banks mostly to use as lagniappe

in trading with other collectors who have mechanical banks I want.

Trading between experienced collectors can sometimes become extremely

sharp, and still banks, I have discovered, make excellent trading

counters for reaching a mutually agreeable exchange.

When I first started, I collected anything that appealed to me. I

still do. But I always try for mint condition. A bank that has been

extensively restored has lost much of its value even if great care has

been exercised. Badly restored banks give themselves away by looking

freshly painted or having crudely joined parts. Whenever I have to have

a bank restored, I cannibalize parts from other banks made during the

same period and I have the work done by a craftsman whose passion for

authenticity matches my own.

Although I value my collection for its condition, I do not worry

about its market value. That's for investors, not collectors. Sometimes,

I must admit, I am shocked to find out how high prices have gone in

recent years. A bank that once sold for $4,500 was bid up to $14,000 in

one sale—and the last price tends to become the floor for the next time

around. That Tammany bank my mother bought in fun in 1952 was selling 25

years later for $130 in good condition. That's expensive for a joke.

Because of the banks' monetary value, some collectors keep theirs

under lock and key. But I like to show mine to other collectors, so I

display them in my office, which is protected with a burglar alarm.

Included in the display is a considerable assemblage of related

materials— patent models, advertising brochures and the original molds

from which the banks were made. I even have a few examples of fake

banks. These are usually mechanical toys to which coin slots were later

added. Then the toys were passed off as true mechanical banks.

Despite its breadth, my collection is simply a source of pleasure

to me, not a scholarly aggregation of artifacts. In fact, I keep a

privately published book in my office for visiting collectors to read:

What I Know about Collecting Mechanical Banks. Its

pages are entirely blank. But my shelves are filled with things I love.

MUSEUMS

The Museum of the City of New York New York, New York 10029

Perelman Antique Toy Museum Philadelphia. Pennsylvania 19106

Seaman's Bank for Savings

New York. New York 10005

BOOKS

Hertz, Louis H., Mechanical Toy Banks,

Mark Haber, 1947.

McCumber, Robert L., Toy Bank Reproductions and Fakes. Published

by the author, 1971.

Meyer. John D., Old Penny Banks: Mechanicals, Stills by Larry

Freeman, Century House. Inc., 1960.

Warman, Edwin G., Mechanicals and Stills Price Guide. E. G.

Warman, 1975.

END |