|

AMERICANA

Magazine, 1989

IN THE MARKETPLACE

BANKS THAT MOVE

Built to hold pennies, they now cost thousands

By Frank Donegan

Mechanical banks are

the aristocrats of the antique-toy world. Created to amuse thrifty children,

they are now the playthings of big-spending collectors. While common

examples sell for a few hundred dollars, prices quickly escalate into the

thousands, and the most desirable banks currently trade at the $250,000

level.

Banks that move when coins are deposited in them have been made since

ancient times. Those most sought by collectors, however, are the whimsical

cast-iron examples produced between the Civil War and the Great Depression,

the golden age of bank making when some two thousand to three thousand

different models were manufactured. Because American collectors are the

largest and freest-spending contingent of bank buyers, banks made by

American companies usually bring more than foreign models.

Major bank collections were first assembled in the 1920's, when some of

the banks were still in production. Although prices have risen strongly

through the 1980's, the recent sale of two major collections showed that

fine banks in pristine condition can bring prices up to twenty times higher

than those of a year or two ago. As Indiana collector Steve Steckbeck says,

"You can't buy any bank for what you paid two years ago."

The more unusual of the two sales was the dispersal of the Perelman Toy

Museum collection at a series of invitation-only tag sales last autumn in

Philadelphia. Leon J. Perelman closed his private museum

— more than five

thousand toys and banks in an eighteenth century town house

— in August

after thieves tied up his curator and made off with a collection of marbles.

He sold the collection and the house to Alex Acevedo, a leading New York

dealer in American paintings who has always been interested in toys, and two

toy and bank dealers, Don Markey of Lititz, Pennsylvania, and Bill Bertoia

of Vineland, New Jersey. They left the collection in its glass showcases,

priced each piece, and held the first tag sale in October. Buyers-given

three hours to examine, but not touch, the collection — had to promise to

spend $50,000.

"Within the first ten minutes there wasn't a bank costing more than

$30,000 left," one participant says; by the end of the day, all but five to

ten percent of the hundreds of banks had been sold. It was a rare patron who

bought only one or two pieces. Michigan collector Stan Sax, for instance,

spent some $600,000 to acquire forty-three banks, including the prized

example called Darky with Watermelon for $245,000. Patented in 1888 and made

by the J. and E. Stevens Company of Cromwell, Connecticut, the leading

American bank maker, it is one of only two known examples. It depicts a

black man kicking a football; when a coin is placed in the football, the man

kicks ball and coin into a watermelon. (Racist stereotypes in most

collectible fields are particularly prized — often by black collectors.) Sax

notes that not only is the Darky with Watermelon bank rare, it has what

collectors call charisma, generally defined as especially interesting

mechanical action.

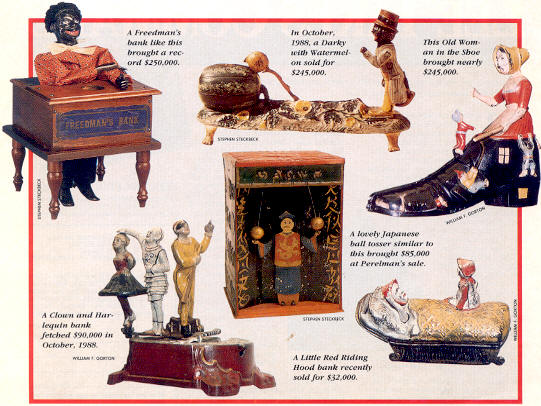

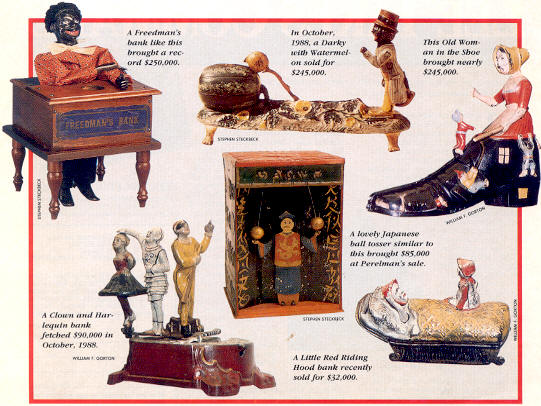

The highest-priced bank of the day went to Oregon collector Frank Kidd,

who paid $250,000 for a Freedman's bank. The metal and wood bank's detail,

paint colors, and action make it particularly valuable —

and only half a dozen

examples are known. Depicting a black man in a striped suit sitting at a

desk, into which he slides a coin, the bank was produced about 1880 by the

Bridgeport, Connecticut, firm of Jerome B. Secor .

Among the banks that sold for less than $100,000

— hardly chea — were

examples showing Little Red Riding Hood, $32,000; a frog hopping along an

arched track, $35,000; a turtle, $30,000; a clown and harlequin, $90,000; a

Japanese ball tosser, $85,000; a dog chasing a cat

— called Seek Him, Frisk

- $70,000; three foot-ball players, $32,000; and a rare King Aqua, $95,000.

Comparing the King Aqua bank (in which a European soldier shoots at an

African in a striped guardhouse) with either the Darky with Watermelon or

Freedman's banks shows the subtleties of this market. The only known example

of King Aqua, this bank is theoretically the rarest in the sale. Steve

Steckbeck explains: "We don't know how many other King Aquas may be out

there, but people have spent lifetimes looking for a Freedman or a Darky

with Watermelon. We know they're rare." Steckbeck also notes that as a

"shooter" bank, the King Aqua falls into a relatively common category.

Finally, it is a European bank by an unknown maker.

Within weeks of its Perelman coup, the Acevedo-Markey-Bertoia trio

bought — and sold — another famous bank collection. Containing more than

three hundred banks assembled between 1925 and 1965 by Gertrude Hegarty and

her late husband, Covert, the collection was legendary. "Some of those banks

had been upgraded twenty times," says Steven Weiss, a partner in the New

York antique-toy firm of Hillman-Gemini. "When an example in better

condition came along, they bought it and sold the example they owned."

Alex Acevedo, the primary financial backer in both sales, says that the

partners had planned to hold another tag sale but ended up selling everything to Al Davidson — owner of a Long Island aluminum company and

author of Penny Lane: A History of Antique Mechanical Toy Banks - for about

$3.2 million.

everything to Al Davidson — owner of a Long Island aluminum company and

author of Penny Lane: A History of Antique Mechanical Toy Banks - for about

$3.2 million.

Davidson reportedly kept some twenty-five banks for himself and quickly

sold off many more for $1.5 - $2 million. Most of those were reportedly

worth less than $50,000 each. Only about half a dozen collectors buy banks

above that level, and some of them seemed to be waiting Davidson out in

hopes of buying at lower prices. Acevedo says, "Some big collectors say that

taking banks out the way Davidson did is taboo. They're sitting back and

biding their time."

Acevedo encountered the same resistance when he proposed to keep one

bank from the Hegarty collection. Called the Moonface, it is a working

prototype of a bank that was never produced because it would have had to

sell for a relatively high price. Not only is the Moonface beautiful, with

careful painting and bronze-like detail in the casting, but it is the

ultimate rarity — a manufactured item that was never manufactured. "When I

said I was going to keep it," Acevedo notes," there was lots of boohooing.

So I quietly put it back." The bank is still for sale, its asking price in

the $300,000 - to - $500,000 range.

Stan Sax is one collector who has not been biding his time. He bought

four banks from the Hegarty collection, including the coveted Old Woman in

the Shoe bank, which, he says, "was almost the same price that I paid for

the Darky bank I bought from Leon Perelman."

The prices realized on Perelman and Hegarty banks emphasize the

importance of condition. Bill Bertoia says, "Condition is everything in this

field. It's like location in real estate." Repairs can cut values in half,

and serious collectors are rarely interested in any bank retaining less than

ninety percent of its original paint. In the area above ninety percent,

subtle differences in condition create huge differences in value. Steven

Weiss explains, "If a bank with ninety percent of its paint is worth $1,000,

then one with ninety-five percent will sell for $2,000, and one that's

ninety-nine percent plus may be worth $5,000." Weiss, who has been working

with Davidson to sell the Hegarty banks, says, "We sold a cabin bank from

Hegarty for $1,500. It's a common bank usually selling for no more than

$500, but this was virtually perfect."

The importance of paint condition has tempted some unscrupulous dealers

and restorers to touch up borderline examples. Although today many serious

collectors own black lights to check for original paint, expert fakers now

reportedly use masking pigments that keep new paint from fluorescing under

black light.

Fakes and reproductions are also a problem. Because cast-iron is

relatively easy to work with, a mold can be made from almost any real bank

to produce copies only a fraction of an inch smaller than the original.

Reproductions have been made since the 1930's, so older ones can be

difficult to distinguish from the real thing (cheaper sand is usually used

in reproductions, whose surfaces have a pebbly look, while early castings

have smooth, precise details). To confuse matters further, period bank parts

are "occasionally discovered, assembled, and painted. A substantial group

of such pieces was reassembled in the 1940's. As their paint ages, only

experts can tell the period bank from the one assembled from period parts.

Legitimate dealers, however, guarantee their banks in writing and offer

buyers return privileges.

The best advice for new collectors is to go slowly. "I'd advise people

to spend a year reading and attending toy shows before they buy their first

bank," says one collector. Successful collectors must learn the

peculiarities and history of each bank: how common it is; how its details

differ from those on reproductions of the same bank; when a paint color is

rare. One common bank, for instance, features a dark painted mule; but the

firm also made a small number with white mules. While the standard version

of that bank sells for $350, the rare variant can bring $3,500.

It may be too early to tell what effect all the activity will

ultimately have on prices. At one recent auction, mediocre banks brought

mediocre prices, while good banks brought high prices. For the moment,

prices of the most expensive banks seem to have leveled off. Three

Freedman's banks, for instance, have sold in the past year, all of them in

the $200,000 to $250,000 range.

High prices at the top (and attendant publicity) seem to be raising

prices at lower levels. Don Markey says, "Banks worth $3,500 are now

bringing $9,500. And just the other day, I got $1,000 for an owl bank that

turns its head. Not long ago I was getting $100 to $150 for it." Markey says

that new collectors are attracted to colorful banks featuring lots of

action, which are often found in the lower reaches of the market because

they were popular in their day and are now common. As Steckbeck says, "If

you needed twenty-five Tammany banks [which depict a fat politician

consuming money], I could get them in a week. And if I pointed to my ten

rarest banks, you'd say, 'Those are really dumb.' That's why they're rare;

they weren't popular in their own time."

Just now, though, every mechanical bank seems to be popular. In today's

market, the rarest of all banks would be the one that nobody wanted.

|

everything to Al Davidson

everything to Al Davidson