|

(Web

note: Scroll down for transcribed text)

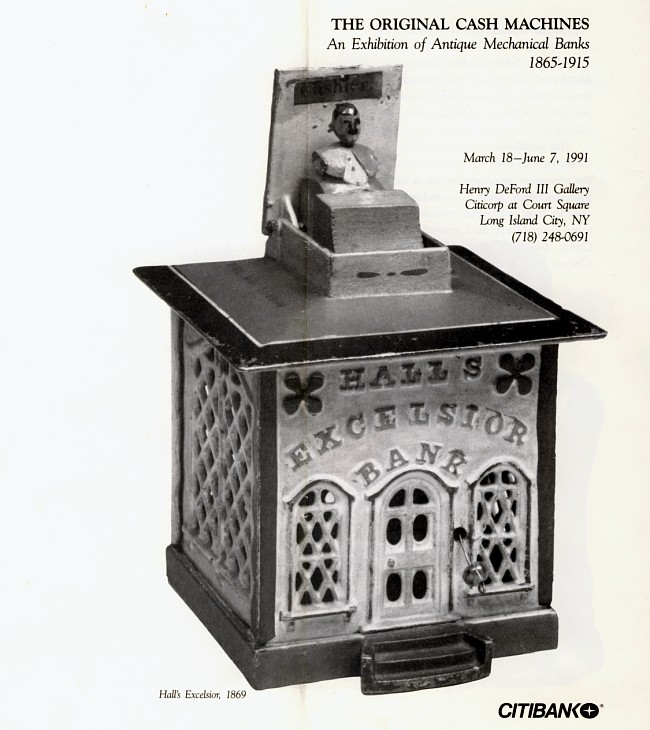

THE ORIGINAL CASH MACHINES

An Exhibition of Antique Mechanical

Banks

1865-1915

March 18 — June 7, 1991

Henry DeFord III Gallery

Citicorp at Court Square

Long Island City, NY

(718) 248-0691

I am pleased and excited to present this exhibition at the Henry DeFord

III Gallery. The focus of "The Original Cash Machines" is a

group of antique mechanical banks together with paintings, prints and

photographs of the era from Citibank's collection.

This exhibition is a direct result of Citibank's Worldwide Art

Inventory project and encourages an ongoing search of the Bank — in closets,

Xerox rooms and even under desks for more unexpected treasures. In July, to

my complete surprise, I received a list from Cynthia Brown of Citibank

Illinois, FSB in Chicago detailing an extensive collection of mechanical

coin banks. I immediately showed this list to Patricia Spergel Bauman, who

recognized from past experience that we had an exceptional group of banks.

Her enthusiasm let to the curating of this exhibition and her good judgment

and excellent eye contribute to its success.

The discovery of these mechanical banks coincided with existing plans

to have Citibank historian Joan L. Silverman organize an exhibition from the

archives. I am grateful to have Joan as a partner in this project to assist

us in bringing this archival material to light for the first time.

Suzanne F.W. Lemakis

Citibank and Post-Civil War America

More than a century before Citibank pioneered cash machines

(ATMs) in the New York metropolitan area, American children stored their

coins in mechanical banks, practicing thrift and amusing themselves at the

same time. School teachers regularly instructed their pupils on the

importance of saving for a rainy day. Benjamin Franklin's maxims about

thrift were part of the popular wisdom: "A penny saved is two pence clear...

For Age and Want, save while you may, no morning sun lasts a whole day." It

was not only Benjamin Franklin who counseled saving. Young people couldn't

help hearing that "A penny saved is a penny got... Without frugality, none

can be rich, and with it very few could be poor." Fortunate, indeed, were

the children who saved their money in these ingenious cast iron marvels —

the original cash machines.

The coin banks on display tell us about American life from the close of

the Civil War to the start of the war we now call World War I. They reflect

the exuberance of an expanding, self-confident country, proud of its new

great power status, its machines and its inventors, as it transformed itself

from an agrarian republic to a mass-production colossus. For indeed

post-Civil War Americans devoted their energies to money making, inspired by

the fiction of Horatio Alger and the true rags-to-riches stories of Andrew

Carnegie and other self-made men.

During this period, Citibank was led by three financial greats who

spearheaded national development in communications, transportation and

financial services. Moses Taylor, a major importer turned industrialist and

financier served as president from 1856 to 1882. Taylor's interests extended

from banking and insurance to gas lighting companies, coal-carrying

railroads and mining, steel production, the transatlantic cable and

telegraph. James Stillman (president from 1891 to 1909 and chairman until

1918) transformed Citibank into America's largest bank. In the panic of

1883. the Bank's superior reputation for safety attracted America's leading

corporations. Under Stillman, the Bank underwrote railroad securities,

participated in rail reorganizations and organized its foreign exchange

department to serve businesses with overseas operations.

In 1908, Citibank moved its office from 52 to 55 Wall Street, after

remodeling the former U.S. Customs House. Frank A. Vanderlip, Stillman's

successor, expanded the Bank's customer base to include smaller U.S. and

foreign firms, foreign governments and retail purchasers of securities.

Vanderlip opened Citibank's first overseas branch in Buenos Aires in 1914

and the following year acquired the International Banking Corporation with

18 overseas branches, paving the way for the global Citibank of today.

Joan L. Silverman

The First Cash Machines

Simple penny banks with no moving parts first appeared in America

around 1793 along with the original large copper penny. Performing toy banks

were first marketed after the Civil War and represent the union of two

fundamentally American traits — thrift and ingenuity. These cast iron banks

were devised by American inventors who coupled fine handicraft with mass

production and created children's toys which reflected the character and

culture of the era.

The toy industry was a thriving part of the U.S. economy by the

mid-1800s and mechanical banks became a major factor in the industry's

continued success. Factories had expanded during the Civil War and a

majority of mechanical banks were manufactured by small iron foundries in

New England, New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio. Although these banks were

initially marketed as children's toys, at about one dollar each, they soon

became popular with adults who began collecting them avidly.

Hall's Excelsior is generally considered the first

cast iron mechanical bank. It was manufactured by J. & E. Stevens Co. of

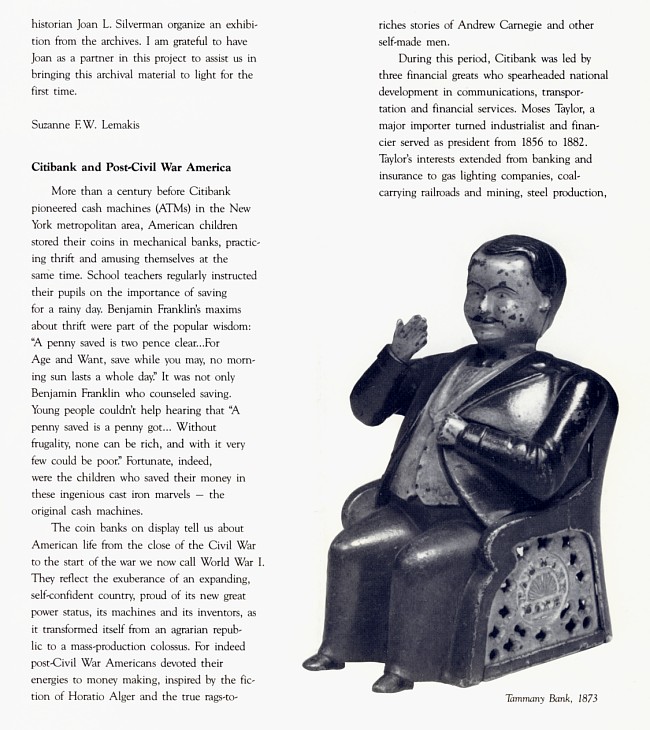

Cromwell, Connecticut and patented in 1869 by John Hall. Tammany

Bank was also designed by John Hall for J. & E. Stevens Co. in

1873. This bank shows a politician slipping money into his pocket and its

action characterizes the political kickbacks which were associated with New

York's Tammany Hall and "Boss" Tweed.

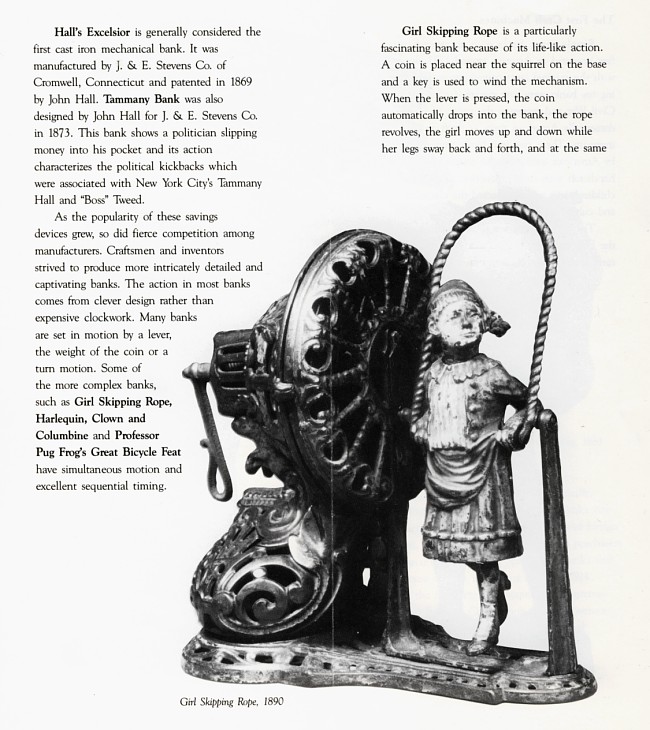

As the popularity of these savings devices grew, so did fierce

competition among manufacturers. Craftsmen and inventors strived to produce

more intricately detailed and captivating banks. The action in most banks

comes from clever design rather than expensive clockwork. Many banks are set

in motion by a lever, the weight of the coin or a turn motion. Some of the

more complex banks, such as Girl Skipping Rope, Harlequin, Clown and

Columbine and Professor Pug Frog's Great Bicycle Feat

have simultaneous motion and excellent sequential timing.

Girl Skipping Rope is a particularly fascinating bank

because of its life-like action. A coin is placed near the squirrel on the

base and a key is used to wind the mechanism. When the lever is pressed, the

coin automatically drops into the bank, the rope revolves, the girl moves up

and down while her legs sway back and forth, and at the same time, she

realistically turns her head from side to side. This is one of the few banks

that was manufactured specifically with girls in mind. It is also

interesting to observe how the structure of this bank echoes the interior

ornamentation of cast iron buildings which achieved their greatest

popularity in American cities during the period 1860 to 1890.

The action in Professor Pug Frog's Great Bicycle Feat

is equally complex. Releasing a spring causes the bicycle-riding frog to

make a complete somersault as he deposits the coin in a basket which a clown

holds before him. At the same time, a music rack is kicked into Mother

Goose's face, causing her tongue to wag.

One of the most popular fads of the Gay Nineties was the national

bicycle craze. The circus. Wild West shows, amusement parks and professional

baseball all drew enthusiastic crowds during this period. The popularity of

these leisure activities is evident in the large group of banks manufactured

with these themes. Even as the urban population burgeoned and the country

rapidly industrialized, Americans waxed nostalgic for life on the farm. The

prevalence of animals in toy banks reflects this longing.

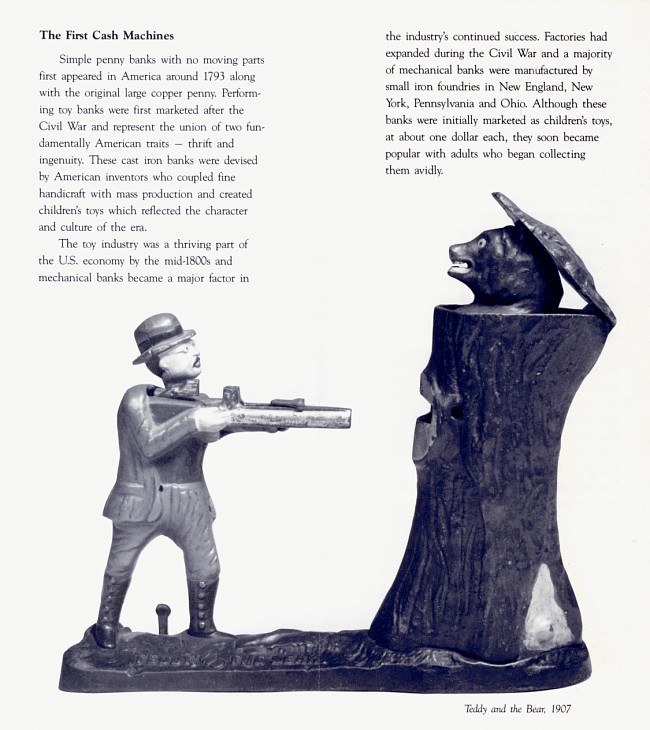

In Teddy and the Bear, the famous politician shoots a

coin into the tree trunk and the head of a grizzly bear emerges from the

top. The story of Teddy Roosevelt and the bear captured national attention

when he reportedly refused to shoot a bear cub while on a hunting trip. The

ever popular "Teddy bear" continues to remind us of this dynamic American

leader.

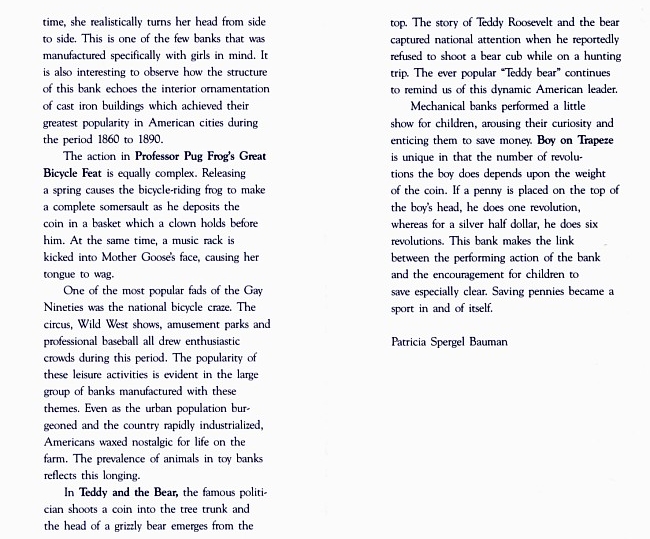

Mechanical banks performed a little show for children, arousing their

curiosity and enticing them to save money. Boy on Trapeze

is unique in that the number of revolutions the boy does depends upon the

weight of the coin. If a penny is placed on the top of the boy's head, he

does one revolution, whereas for a silver half dollar, he does six

revolutions. This bank makes the link between performing action of the bank

and the encouragement for children to save especially clear. Saving pennies

became a sport in and of itself.

Patricia Spergel Bauman

Many people helped to make this exhibition a reality:

Ira Rimerman, Nathaniel Sutton, Henry Ehrlich, Ruthie Roberts, Anita

Grossman, Chris Craigo, Ramona Jan, Natasha Devlin, Cesar Pimentel, Herb

Glick, Alan Wilson, Ken Sakacs, Michael Focar, Nancy Speer, Cheryll Resch,

Kenny Vollweiler, Shirley Dutton and of course, a special thanks to all of

the people at Citibank Illinois, FSB in Chicago and especially Bill Atwell,

Patrick Morgan, Cynthia Brown and Howard Lindgren, for their generosity in

lending us this fabulous collection.

The Henry FeFord III Gallery was named in honor of the late Hal DeFord,

whose leadership of Citibank's Real Property Services will be remembered

always.

Photography: Michael Tropea, Chicago

Hall's Excelsior, 1869

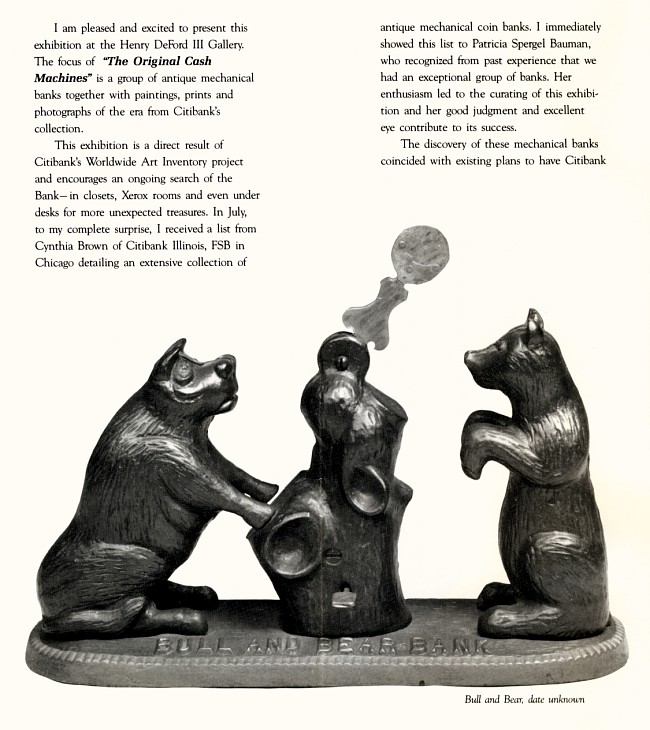

Bull and Bear, date unknown

Tammany Bank, 1873

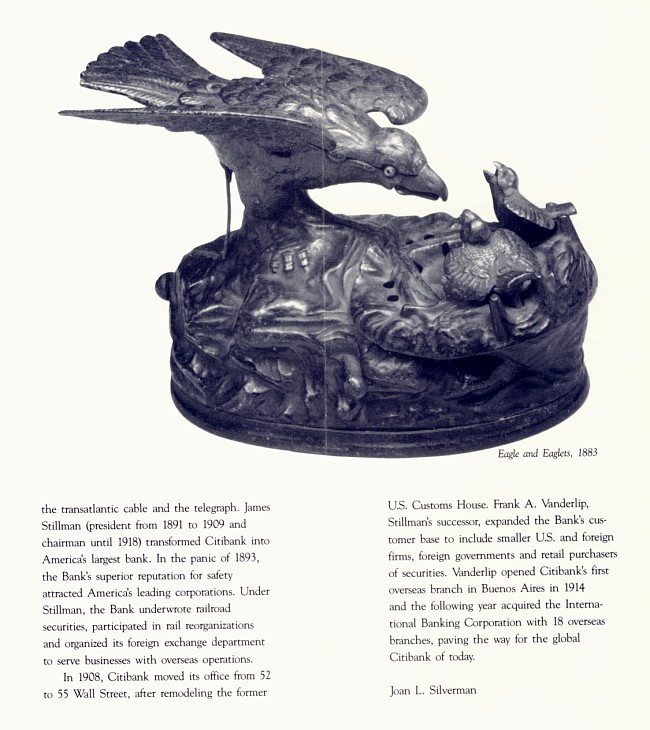

Eagle and Eaglets, 1883

Teddy and the Bear, 1907

Girl Skipping Rope, 1890

|