|

TRADITIONAL HOME HOLIDAY 1994

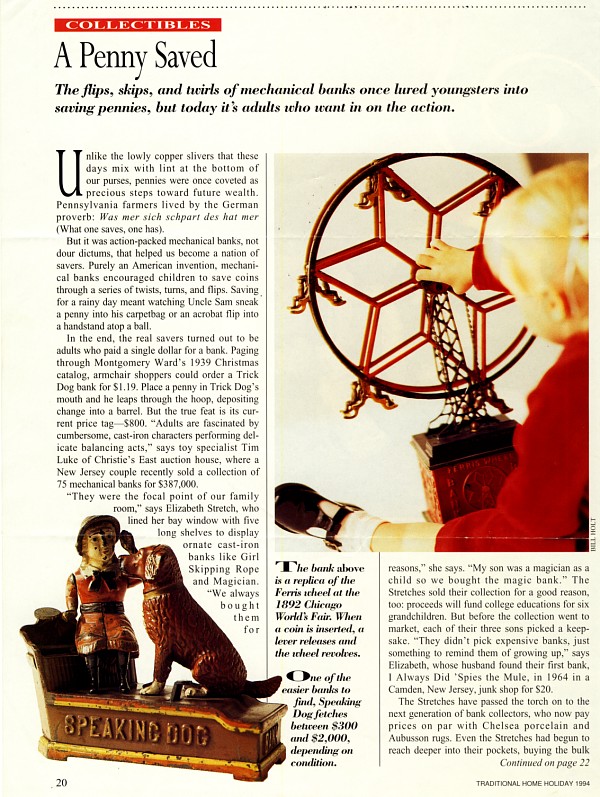

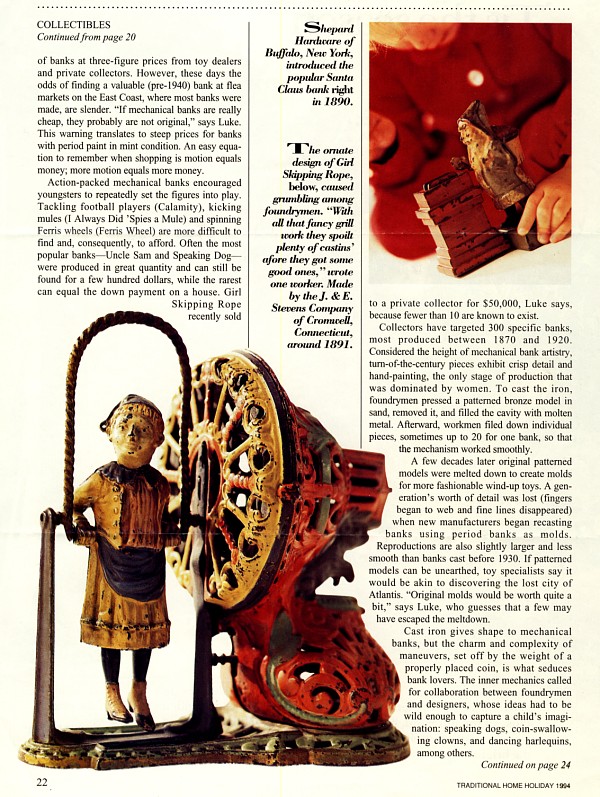

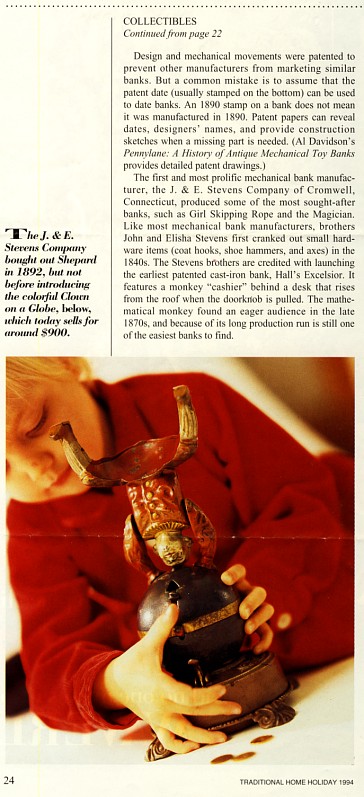

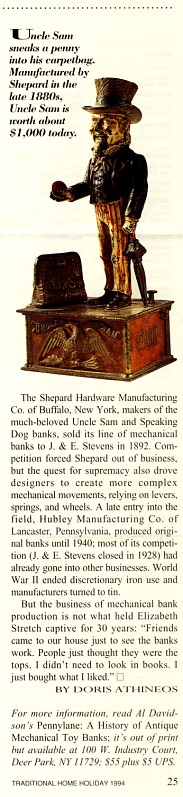

(Web Note: see page scans below for photos) COLLECTIBLES A Penny Saved The flips, skips, and twirls of mechanical banks once lured youngsters into saving pennies, but today it's adults who want in on the action. Unlike the lowly copper slivers that these days mix with lint at the bottom of our purses, pennies were once coveted as precious steps toward future wealth. Pennsylvania farmers lived by the German proverb: Was mer sich schpart des hat mer (What one saves, one has). But it was action-packed mechanical banks, not dour dictums, that helped us become a nation of savers. Purely an American invention, mechanical banks encouraged children to save coins through a series of twists, turns, and flips. Saving for a rainy day meant watching Uncle Sam sneak a penny into his carpetbag or an acrobat flip into a handstand atop a ball. In the end, the real savers turned out to be adults who paid a single dollar for a bank. Paging through Montgomery Ward's 1939 Christmas catalog, armchair shoppers could order a Trick Dog bank for $1.19. Place a penny in Trick Dog's mouth and he leaps through the hoop, depositing change into a barrel. But the true feat is its current price tag — $800. "Adults are fascinated by cumbersome, cast-iron characters performing delicate balancing acts," says toy specialist Tim Luke of Christie's East auction house, where a New Jersey couple recently sold a collection of 75 mechanical banks for $387,000. "They were the focal point of our family room," says Elizabeth Stretch, who lined her bay window with five long shelves to display ornate cast-iron banks like Girl Skipping Rope and Magician. "We always bought them for reasons," she says. "My son was a magician as a child so we bought the magic bank." The Stretches sold their collection for a good reason, too: proceeds will fund college educations for six grandchildren. But before the collection went to market, each of their three sons picked a keepsake. "They didn't pick expensive banks, just something to remind them of growing up," says Elizabeth, whose husband found their first bank, I Always Did 'Spise the Mule, in 1964 in a Camden, New Jersey, junk shop for $20. The Stretches have passed the torch on to the next generation of bank collectors, who now pay prices on par with Chelsea porcelain and Aubusson rugs. Even the Stretches had begun to reach deeper into their pockets, buying the bulk of banks at three-figure prices from toy dealers and private collectors. However, these days the odds of finding a valuable (pre-1940) bank at flea markets on the East Coast, where most banks were made, are slender. "If mechanical banks are really cheap, they probably are not original," says Luke. This warning translates to steep prices for banks with period paint in mint condition. An easy equation to remember when shopping is motion equals money; more motion equals more money. Action-packed mechanical banks encouraged youngsters to repeatedly set figures into play. Tackling football players (Calamity), kicking Mules (I Always Did 'Spies a Mule) and spinning Ferris wheels (Ferris Wheel) are more difficult to find and, consequently, to afford. Often the most popular banks — Uncle Sam and Speaking Dog — were produced in great quantity and can still be found for a few hundred dollars, while the rarest can equal the down payment on a house. Girl Skipping Rope recently sold to a private collector for $50,000, Luke says, because fewer than 10 are known to exist. Collectors have targeted 300 specific banks, most produced between 1870 and 1920. Considered the height of mechanical bank artistry, turn-of-the-century pieces exhibit crisp detail and hand-painting, the only stage of production that was dominated by women. To cast the iron, foundrymen pressed a patterned bronze model in sand, removed it, and filled the cavity with molten metal. Afterward, workmen filed down individual pieces, sometimes up to 20 for one bank, so that the mechanism worked smoothly. A few decades later original patterned models were melted down to create molds for more fashionable wind-up toys. A generation's worth of detail was lost (fingers began to web and the fine lines disappeared) when new manufacturers began recasting banks using period banks as molds. Reproductions are also slightly smaller and less smooth than banks cast before 1930. If patterned models can be unearthed, toy specialists say it would be akin to discovering the lost city of Atlantis. "Original molds would be worth quite a bit," says Luke, who guesses that a few may have escaped the meltdown. Cast iron gives shape to mechanical banks, but the charm and complexity of maneuvers, set off by the weight of a properly placed coin, is what seduces bank lovers. The inner mechanics called for collaboration between foundrymen and designers, whose ideas had to be wild enough to capture a child's imagination: speaking dogs, coin swallowing clowns, and dancing harlequins, among others. Design and mechanical movements were patented to prevent other manufacturers from marketing similar banks. But a common mistake is to assume that the patent date (usually stamped on the bottom) can be used to date banks. An 1890 stamp on a bank does not mean it was manufactured in 1890. Patent papers can reveal dates, designers' names, and provide construction sketches when a missing part is needed. (Al Davidson's Pennylane: A History of Antique Mechanical Toy Banks provides detailed patent drawings.) The first and most prolific mechanical bank manufacturer, the J. & E. Stevens Company of Cromwell, Connecticut, produced some of the most sought-after banks, such as Girl Skipping Rope and the Magician. Like most mechanical bank manufacturers, brothers John and Elisha Stevens first cranked out small hardware items (coat hooks, shoe hammers, and axes) in the 1840's. The Stevens brothers are credited with launching the earliest patented cast-iron bank, Hall's Excelsior. It features a monkey "cashier" behind a desk that rises from the roof when the doorknob is pulled. The mathematical monkey found eager audience in the late 1870s, and because of its long production run is still one of the easiest banks to find. The Shepard Hardware Manufacturing Co. of Buffalo, New York, makers of the much beloved Uncle Sam and Speaking Dog banks, sold its line of mechanical banks to J. & E. Stevens in 1892. Competition forced Shepard out of business, but the quest for supremacy also drove designers to create more complex mechanical movements, relying on levers, springs, and wheels. A late entry into the field, Hubley Manufacturing Co. of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, produced original banks until 1940; most of its competition (J. & E. Stevens closed in 1928) had already gone into other businesses. World War II ended discretionary iron use and manufacturers turned to tin. But the business of mechanical bank production is not what held Elizabeth Stretch captive for 30 years: "Friends came to our house just to see the banks work. People just thought they were the tops. I didn't need to look in books. I just bought what I liked." BY DORIS ATHINEOS For more information, read Al Davidson's Pennylane: A History of Antique Mechanical Toy Banks; it's out of print but available at 100 W. Industry Court, Deer Park, NY 11729, $55 plus $5 UPS. Captions for photos (see page scans below) 1) The bank above is a replica of the Ferris wheel at the 1892 Chicago World's Fair. When a coin is inserted, a lever releases and the wheel revolves. 2) One of the easier banks to find, Speaking Dog fetches between $300 and $2,000, depending on condition. 3) Shepard Hardware of Buffalo, New York, introduced the popular Santa Claus bank right in 1890. 4) The ornate design of Girl Skipping Rope, below, caused grumbling among foundrymen. "With all that fancy grill work they spoilt plenty of castins' afore they got some good ones," wrote one worker. Made by the J. & E. Stevens Company of Cromwell, Connecticut, around 1891. 5) The J. & E. Stevens Company bought out Shepard in 1892, but not before introducing the colorful Clown on a Globe, below, which today sells for around $900. 6) Uncle Sam sneaks a penny into his carpetbag. Manufactured by Shepard in the late 1880s, Uncle Sam is worth about $1,000 today |

|