BOSTON SUNDAY GLOBE, July 23, 1978, page 45

ANTIQUES FOR TODAY

Those old toy banks: You

could have banked on them

Special to The Globe

More and more people are

putting their money into banks these days — old penny or "piggy"

banks, that is.

They're discovering that the little toy banks, given to

children years ago to help teach them thrift, sometimes can provide bigger

dividends than money in real banks.

|

"Tammany' is one of the most common mechanical banks as it was made from the mid-1870's into the 1920s. Yet this bank, depicting a dishonest politician, who pockets coins while nodding thanks, sells today anywhere from $100 to $300, depending on condition. |

For example, little

banks in the forms of animals that used to sell for a nickel or dime around the

turn-of-the-century are now worth $50 and more. Mechanical banks that cost 50 to

75 cents in the late 1800s and early 1900s today are commanding in the hundreds

of dollars.

Prices of these banks, that were so commonplace in

their day, climbed gradually during the first half of this century, but after

World War II they really took off.

What has happened to the William Tell, one of the

nicest of shooting banks, is typical of what has happened price-wise to these

erstwhile playthings which are so prized today by collectors.

The William Tell mechanical bank, which has the apple

fall from the little boy's head, deposit a penny in the castle and ring a bell

just by pressing the marksman's foot, sold for under $1 when it first came out

in the 1890's. After World War II it had climbed in price to around $16. By 1952

it was selling for $25. Three years later for $75; by 1969 it was commanding as

much as $120 and today collectors are paying as much as $300 for a William Tell

bank.

Even so, that's petty cash compared to the prices paid

for some old banks.

Just last month in the Art and Antiques Weekly of the

Newtown Bee, published in Connecticut, a Virginia collector ran a "Wanted:

Mechanical Banks" advertisement in which he offered to pay $15,000 for the

cast-iron bank, called "Moonface."

Actually it's not unusual for a very rare bank to

command a five-figure price.

But that those figures shouldn't discourage anyone who

is interested in getting started in this area of collecting. There are still

many banks that can be bought for small sums, some even for under $10.

Generally speaking, the two kinds of cast iron banks

that are being collected today are the mechanical and the still banks. The

mechanicals are activated by the drop of a coin whereas the still bank does not

have any moving parts. The cast iron banks sought by collectors date from the

1870s until around 1910.

Before John Hall of Watertown patented his "toy

safe" in 1869, which was manufactured in the 1870s by the J. & E.

Stevens Co. of Cromwell, Conn., their coin banks.

But, instead of cast iron, they were made of

earthenware, glass and tin. However, few of these have survived and those that

have are mostly in museum collections today.

One of the reasons old banks are so intriguing is that

there is such a variety of forms that one can collect; animals, people, houses,

buildings, furniture, birds, bells, vehicles, caricatures, safes, ferris wheels,

music boxes. You name it, and you'll find it's probably been fashioned into a

bank.

Some people collect in just one category. Others like

to search for as many forms as they can find.

The person who has what is probably the finest

collection of coin banks in the world is Edwin H. Mosler Jr. of New York, the

retired chairman of the Mosler Safe Co. and great-grandson of the founder. He

says that although he has been collecting for more than 25 years there are still

at least three great banks that he has not been able to purchase as yet. They

are The Preacher in the Pulpit, The Old Woman In A Shoe and The Japanese Ball

Tosser.

The last, manufactured in the late 1880's in New

Bedford by The Weeden Manufacturing Co., is extremely rare. But the bank that is

considered to be the rarest and most desirable of all mechanical banks,

Freedman's Bank, is in Mosler's collection.

Only a handful of Freedman banks have been uncovered

over the years and only one can be seen by the public, that at the Perelman

Antique Toy Museum in Philadelphia.

This bank is so rare because it was manufactured for

only about five years, from 1878 to 1883, and it was the only bank that Jerome B

Secor of Bridgeport, Conn., a sewing machine manufacturer, made.

Another reason it is so prized is because of its superb

mechanism. First you wind it up with a key. Then you place a coin on the wooden

table and press a lever on the side. The smiling Freedman in his cloth suit and

pussycat bow tie, slides the penny into the bank's opening with his left hand

while at the same time he raises his right arm and arrogantly thumbs his nose

while nodding his head.

As Carole Rogers, author of "Penny Banks: A

History and a Handbook," a Dutton Paperback points out: "There are two

criteria that determine the value of a particular mechanical bank to a

collector. Its action and its rarity."

Freedman's Bank combines both action and rarity.

The ideal, of course, is to buy banks in mint

condition, that is, with no missing or replaced parts and with original paint,

Rogers explains.

"As a practical matter that is not always

possible. A bank that has been repaired, even if a part has been replaced, does

not lose all its value if the work was carefully done. A bank that has been

repainted is usually a bad investment.

In her book, an indispensable guide written especially

for collectors, Rogers gives guideposts for determining whether that old bank is

really old, or whether it is a recast., a reproduction or a fake, that is, a

mechanical toy that may have been converted into a mechanical bank.

If you have limited funds, you probably would do better

to collect still banks. Not only would you have a wider range of items from

which to choose but also the prices for still banks are lower.

However, still bank collectors, like mechanical bank

collectors, must be wary of reproductions, warns Rogers.

"Many of the reproductions are sold openly as

such. Others are occasionally passed off as originals."

The same criteria that distinguish genuine mechanical

banks from the reproduced banks also apply to still banks, she points out.

"The old castings were excellent. The detail is

clear and sharp. The pieces fit together tightly. The old banks feel smooth and

satiny. The reproductions on the other hand, have a rough and pebbly surface.

The details are blurred and the pieces fit together improperly."

Besides "Penny Banks," the first book to give

both the history of the subject and to illustrate it with more than 100

halftones and more than 30 color subjects, other must reading for anyone

interested in collecting banks includes Hubert B. Whiting's "Old Iron Still

Banks" and F. H. Griffith's "Mechanical Banks."

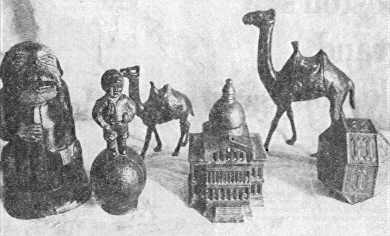

Cast-iron still banks, designed for children,

were sold in general

stores in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for under $. But

prices since then have skyrocketed as can be seen from the tags

on these old banks from the Bournedale Country Store, Herring

Pond Rd., Bourne. Left to right, a caricature of Gen, Benjamin F.

Butler, about $600; baseball player, about $100; camel, $75;

Massachusetts State House, around $500; large camel, $150;

and rare alphabet bank, about $700.

(Globe Photo by Paul Connell)

Some people put their money