| NRTA JOURNAL, November – December, 1981

Toys that weren’t thrown out

These charming playthings preserved in a Philadelphia

museum provide an insight into life in early America

By Doris Wilson Weinsheimer

Entering the Perelman Antique Toy Museum in Philadelphia takes you a

giant step back in time – to America’s childhood.

Here are more than 3,000 of America’s earliest mechanical and

cast-iron toys. Once in abundance, they are now some of the rarest. Soldered

by hand, most were hand-painted by girls in toy factories between 1840 and

1860.

There’s a tin buggy and horse. Wind it and the horse trots while the legs of

a man flail back and forth behind the wagon. There are animated butchers,

bakers and, yes, candlestick makers. There are merry-go-rounds that can

still spin their horses and their riders.

There are tin animals that run, tin birds that hop and stagecoaches

that were all wound and rewound by children long ago.

Some cast-iron toys that had cost the unheard-of sum of a dollar when new

are now valued at up to $200.

The fascinating collection, including an 1820 baby’s rattle and a

cast-iron miniature of Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, began in

1958 when a native-born Philadelphia industrialist, Leon J. Perelman, ambled

into a hobby show in Iowa.

“I was on a business trip,” he explains, “and had a few minutes of

spare time.”

A display of mechanical banks caught his eye, and he spent the entire

afternoon dropping pennies in each and studying their ingenious mechanisms.

“Before that,” he says, “I had left collecting to the collectors. But the

banks hooked me and I knew I had to have as many as I could possibly find.”

He haunted antique shops, shows, and junk stores, scoured friends’

attics and strangers’ basements.

“In seven years, my bank collection grew tremendously,” he adds. “And

so did my legion of cast-iron and tin toys, both animated and still.”

Closets bulged in Perelman’s home; his attic was full and so was his

garage.

Eventually, he realized he had to share his unusual collection of early

Americana with the public. He searched Philadelphia’s old Society Hill

section for a suitable museum site.

“The area was in the throes of refurbishing,” he says, “and I

suffered many a stubbed toe stumbling over debris and old bricks. But I

finally found the perfect place.”

It was the two-centuries-old Abercrombie house at 270 South Second

Street. A warehouse for years, it was a shambles.

“But it still had the dignity that its builder, Captain James

Abercrombie Sr., had meant it to have,” Perelman explains. “And I knew that

my antique toys belonged there.”

Restoration of the five-story building took two years, The Perelman

Antique Toy Museum opened in 1969. Every week, more than 300 visitors, from

five to 95, sign the log book.

Many have fun dropping pennies into reproductions of four

once-popular banks. There’s P. T. Barnum’s “Jumbo,” who holds a penny in his

trunk until his tail is tipped to shoot the coin into a box on his back. A

flick of a button and a horse, penny between his rear hooves, rears up and

shoots it into a tiny iron stable.

With another bank, a twist of a cast-iron monkey’s tail tosses a

penny into a gayly painted organ grinder’s hat. With another, you put a

penny into a dapper, thumb-sized iron figure’s hand and touch a button – he

swishes it into a tiny bank building, deposits it and swooshes out again.

There are shiny steam engines and bell-ringing fire engines, drab

police wagons and gaudy, colored circus carts. Tiny trumpeters toot horns

from a tiny chariot. Miniature iron people are both drivers and passengers.

There are toy trains of all sizes, and ships, boats and early airplanes.

“It’s like looking at America’s history of transportation as it

bumped along the rutty road of development from an open buckboard to a

slick, black Model-T Ford,” says Perelman.

Many of the cast-iron animated toys are amusing. A tiny Ulysses S.

Grant, seated comfortably in a chair, turns his head and puffs out smoke; a

preacher in a pulpit exhorts his flock; a minstrel man swings cymbals in his

hands. A little wind-up girl plays the piano, and wind-up policemen

fast-peddle their bikes after imaginary culprits.

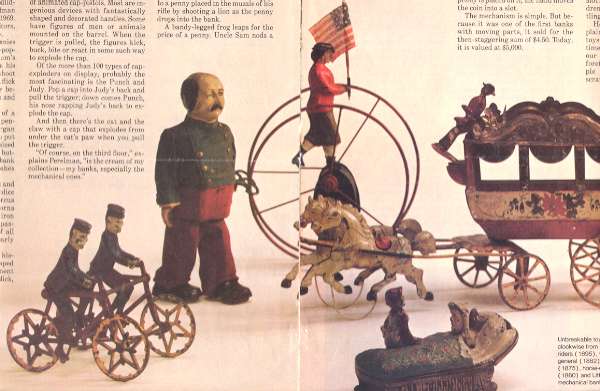

The museum has a rare collection of animated cap-pistols. Most are

ingenious devices with fantastically shaped and decorated handles. Some have

figures of men or animals mounted on the barrel. When the trigger is pulled,

the figures kick, buck, bite or react in some such way to explode the cap.

Of the more than 100 types of cap-exploders on display, probably the

most fascinating is the Punch and Judy. Pop a cap into Judy’s back and pull

the trigger; down comes Punch, his nose rapping Judy’s back to explode the

cap.

And then there’s the cat and the claw with a cap that explodes from under

the cat’s paw when you pull the trigger.

“Of course, on the third floor,” explains Perelman, “is the cream of

my collection – my banks, especially the mechanical ones.”

Here, a grand array of tiny figures come to life for a penny and a

press of a lever.

A grandmotherly mask flies off of Red Riding Hood’s wolf, disclosing

a fangy beast. A petite ballerina spins from harlequin to harlequin. A small

girl skips rope, turning her head from side to side. Jonah, safe in a small

boat, pops a penny into the whale’s mouth. A cocky Teddy Roosevelt, on

safari in Africa, responds to a penny placed in the muzzle of his rifle by

shooting a lion as the penny drops into the bank.

A bandy-legged frog leaps for the price of a penny. Uncle Sam nods a

“thank you” when a coin is placed in his outstretched hand, then he slips it

into his carpetbag.

And there’s the William Tell bank, which uses a real cap to explode

when Tell fires a penny at an apple on his son’s head.

“Each of these banks was patented before World War I,” says Perelman.

“Although they

aren’t so terribly old, they are as hard to find as the proverbial hen’s

teeth. This is because so many were donated for scrap during that war.”

Of the 243 known types of mechanical banks that began appearing in

1867, Perelman has acquired 235, making his collection the largest in the

world.

It includes one of the rare Freedman banks. Only six were believed to have

been made in 1867. A figure sits at a giant wooden table. When a penny is

placed on it, the hand moves the coin into a slot.

The mechanism is simple. But because it was one of the first banks

with moving parts, it sold for the then-staggering sum of $4.50. Today, it

is valued at $5,000.

Has the Freedman completed Perelman’s search for antique toys?

“Certainly not,” he replies. “Since all of the toys are in their original

condition, I’m constantly looking for ones in as near mint shape as

possible.”

And he’s also seeking an exceedingly rare bank – the Old Woman In The

Shoe. It is, of course, a large shoe, surrounded by a host of youngsters and

an old woman. A coin placed in a slot and a lever pressed sends the children

into motion – pushing and jostling each other.

He’s seeking it because, as he explains, “Toys of yesteryear, like

the toys of today, are the signs of the times. They’re our history. They’re

our heritage. They represent our forefathers . . . you know, those people

who built our country from scratch.”

|