|

The Monkey and Cocoanut Bank

by Sy Schreckinger – ANTIQUE TOY WORLD Magazine – April, 1990

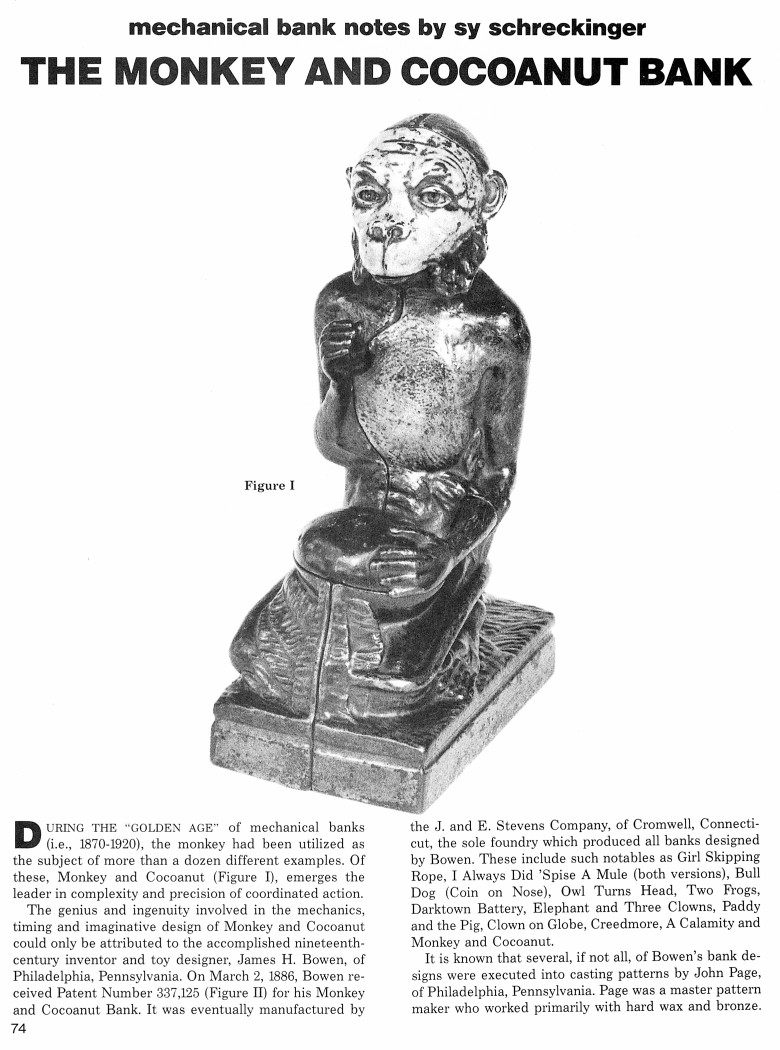

During the “Golden Age” of mechanical banks

(i.e., 1870-1920), the monkey had been utilized as the subject of more

than a dozen different examples. Of' these, Monkey and Cocoanut (Figure

I), emerges the leader in complexity and precision of coordinated action.

The genius and ingenuity involved in the mechanics, timing and

imaginative design of Monkey and Cocoanut could only be attributed to the

accomplished nineteenth-century inventor and toy designer, James H. Bowen,

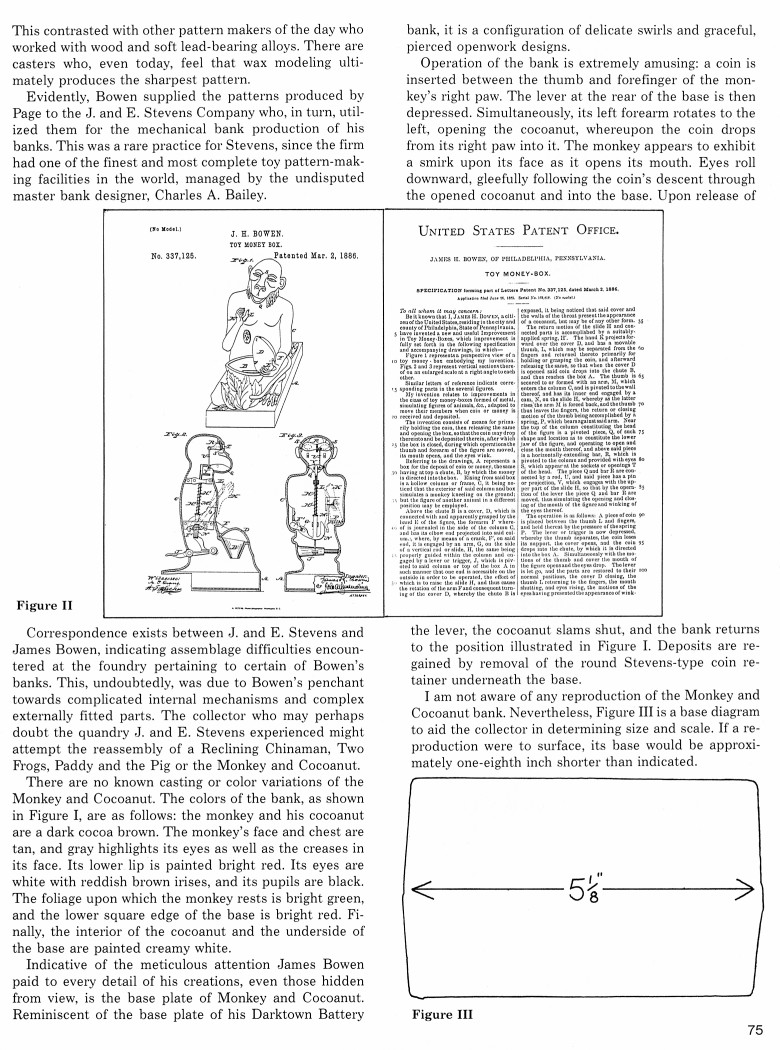

of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On March 2, 1886, Bowen received Patent

Number

337,125 (Figure II) for his Monkey and Cocoanut Bank. It was

eventually manufactured by the J. and E. Stevens Company, of Cromwell,

Connecticut, the sole foundry which produced all banks designed by Bowen.

These include such notables as Girl Skipping Rope, I Always Did 'Spise A

Mule (both versions), Bull Dog (Coin on Nose), Owl Turns Head, Two Frogs,

Darktown Battery, Elephant and Three Clowns, Paddy and the Pig, Clown on

Globe, Creedmore, A Calamity and Monkey and Cocoanut.

It is known that several, if not all, of Bowen's bank designs were

executed into casting patterns by John Page, of Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania. Page was a master pattern maker who worked primarily with

hard wax and bronze. This contrasted with other pattern makers of' the day

who worked with wood and soft lead-bearing alloys. There are casters who,

even today, feel that wax modeling ultimately produces the sharpest

pattern.

Evidently, Bowen supplied the patterns produced by Page to the J. and

E. Stevens Company who, in turn, utilized them for the mechanical bank

production of his banks. This was a rare practice for Stevens, since the

firm had one of the finest and most complete toy pattern-making facilities

in the world, managed by the undisputed master bank designer, Charles A.

Bailey.

Correspondence exists between J. and E. Stevens and James Bowen,

indicating assemblage difficulties encountered at the foundry pertaining

to certain of Bowen's banks. This, undoubtedly, was due to Bowen's

penchant towards complicated internal mechanisms and complex externally

fitted parts. The collector who may perhaps doubt the quandary J. and E.

Stevens experienced might attempt the reassembly of a Reclining Chinaman,

Two Frogs, Paddy and the Pig or the Monkey and Cocoanut.

There are no known casting or color variations of the Monkey and

Cocoanut. The colors of the bank, as shown in Figure I, are as follows:

the monkey and his cocoanut are a dark cocoa brown. The monkey's face and

chest are tan, and gray highlights its eyes as well as the creases in its

face. Its lower lip is painted bright red. Its eyes are white with reddish

brown irises, and its pupils are black. The foliage upon which the monkey

rests is bright green, and the lower square edge of the base is bright

red. Finally, the interior of the cocoanut and the underside of the base

are painted creamy white.

Indicative of the meticulous attention James Bowen paid to every

detail of his creations, even those hidden from view, is the base plate of

Monkey and Cocoanut. Reminiscent of the base plate of his Darktown Battery

bank, it is a configuration of' delicate swirls and graceful, pierced

openwork designs.

Operation of the bank is extremely amusing: a coin is inserted

between the thumb and forefinger of the monkey's right paw. The lever at

the rear of the base is then depressed. Simultaneously, its left forearm

rotates to the left, opening the cocoanut, whereupon the coin drops from

its right paw into it. The monkey appears to exhibit a smirk upon its face

as it opens its mouth. Eyes roll downward, gleefully following the coin's

descent through the opened cocoanut and into the base. Upon release of the

lever, the cocoanut slams shut, and the bank returns to the position

illustrated in Figure I. Deposits are regained by removal of the round

Stevens-type coin retainer underneath the base.

I am not aware of any reproduction of the Monkey and Cocoanut bank.

Nevertheless, Figure III is a base diagram to aid the collector in

determining size and scale. If a reproduction were to surface, its base

would be approximately one-eighth inch shorter than indicated.

|