|

The Freedman’s Bank

by Sy Schreckinger – ANTIQUE TOY WORLD Magazine – July, 1997

The Civil War had ended, and multitudes of

liberated Negroes were bewildered and perturbed as they faced an uncertain

future. Ill-prepared to deal with their newly acquired independence and

accompanying responsibilities, Blacks turned to a government agency

entitled the "Freedmen's Bureau." The purpose of this organization was to

aid needy free men through education, acquisition of jobs, settlement of

homesteads on deserted and confiscated lands, and protection of civil

rights.

On March 3, 1865, concurrent with the establishment of the Freedmen's

Bureau, Congress chartered the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company. Its

purpose was twofold: to encourage savings and budgeting amongst the new

African-American work force and, most importantly, to protect this group

from the hordes of unscrupulous private bankers eager to pilfer their

earnings. Figure 1 is a depiction of an original Freedman's Savings and

Trust dividend check. Each certificate bore the likeness of Abraham

Lincoln, an image the freedman equated with honesty, trust, and integrity.

However, despite all good intentions, both the Freedman's Savings and

Trust Company and the Freedmen's Bureau proved impotent and inept. Blacks

continued to fall prey to Southern white racism. Anti-Black lobbies

within the government continued to prevent the freedmen from making any

significant inroads into the "free" American society. African-American

resentment grew nationwide.

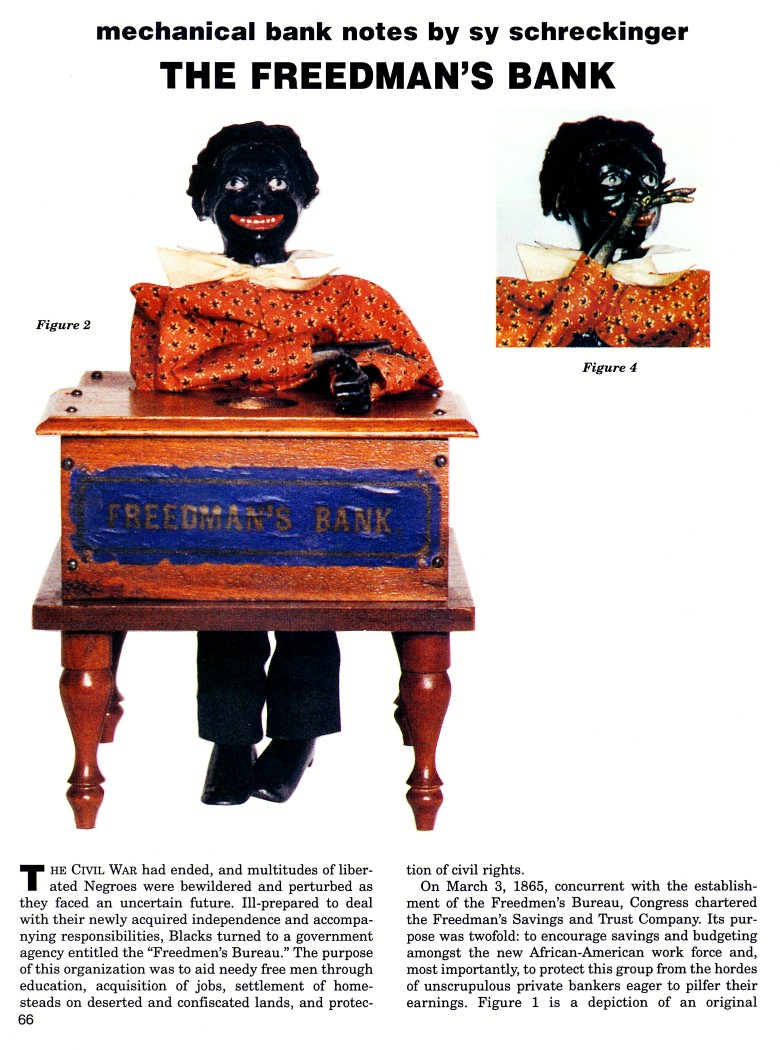

Utilizing these emotions and historical events, paramount inventor,

designer, and toy manufacturer Jerome B. Secor, of Bridgeport, Conn.,

designed a bank that demonstrated the growing Black dissatisfaction. His

creation was christened the "Freedman's Bank," and is seen in Figure 2.

An early advertising flyer for the "Freedman's Bank" is seen in

Figure 3. The price of each bank is indicated as a whopping $4.50. Since

the average workingman's salary was approximately 20 cents per day, this

leaves no doubt as to the object of Secor's intended market.

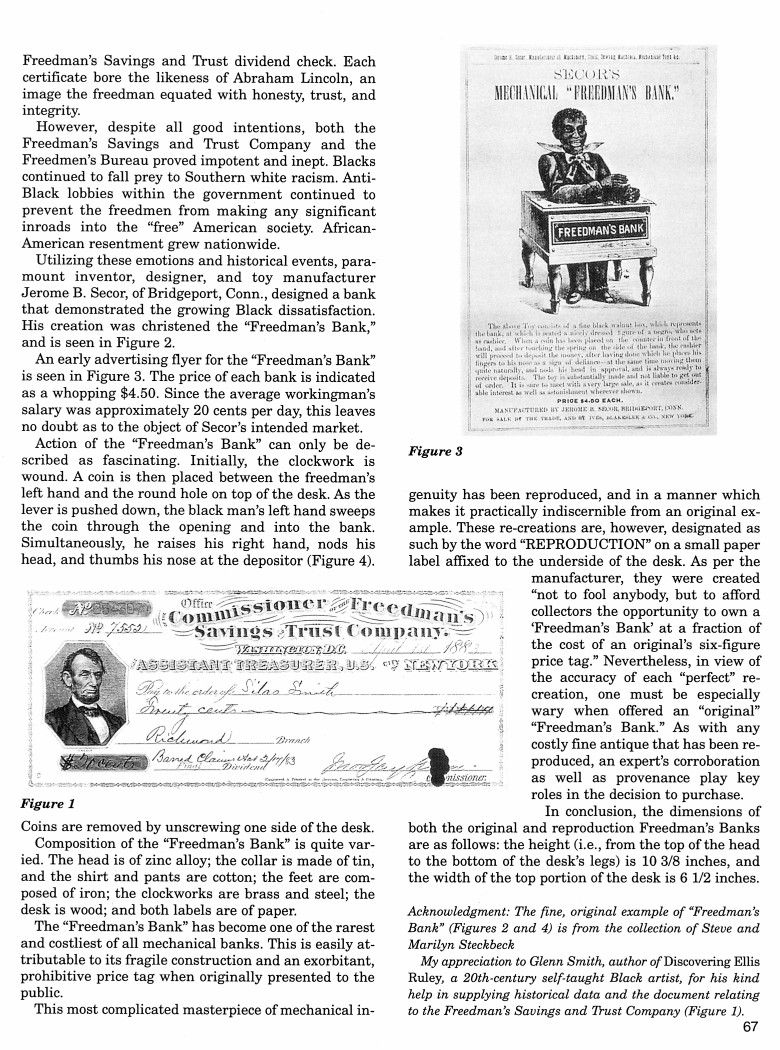

Action of the "Freedman's Bank" can only be described as fascinating.

Initially, the clockwork is wound. A coin is then placed between the

freedman's left hand and the round hole on top of the desk. As the lever

is pushed down, the black man's left hand sweeps the coin through the

opening and into the bank. Simultaneously, he raises his right hand, nods

his head, and thumbs his nose at the depositor (Figure 4). Coins are

removed by unscrewing one side of the desk.

Composition of the "Freedman's Bank" is quite varied. The head is of

zinc alloy; the collar is made of tin, and the shirt and pants are cotton;

the feet are composed of iron; the clockworks are brass and steel; the

desk is wood; and both labels are of paper.

The "Freedman's Bank" has become one of the rarest and costliest of

all mechanical banks. This is easily attributable to its fragile

construction and an exorbitant, prohibitive price tag when originally

presented to the public.

This most complicated masterpiece of mechanical ingenuity has been

reproduced, and in a manner which makes it practically indiscernible from

an original example. These re-creations are, however, designated as such

by the word "REPRODUCTION" on a small paper label affixed to the underside

of the desk. As per the manufacturer, they were created "not to fool

anybody, but to afford collectors the opportunity to own a 'Freedman's

Bank' at a fraction of the cost of an original's six-figure price tag."

Nevertheless, in view of the accuracy of each "perfect" recreation, one

must be especially wary when offered an "original" "Freedman's Bank." As

with any costly fine antique that has been reproduced, an expert's

corroboration as well as provenance play key roles in the decision to

purchase.

In conclusion, the dimensions of both the original and reproduction

Freedman's Banks are as follows: the height (i.e., from the top of the

head to the bottom of the desk's legs) is 10-3/8 inches, and the width of

the top portion of the desk is 6-1/2 inches.

Acknowledgment: The fine, original example of "Freedman's Bank"

(Figures 2 and 4) is from the collection of Steve and Marilyn Steckbeck.

My appreciation to Glenn Smith, author of Discovering Ellis Ruley, a

20th-century self-taught Black artist, for his kind help in supplying

historical data and the document relating to the Freedman's Savings and

Trust Company (Figure 1).

|